I've said it before and I'll say it again, Trailblazer guides take some beating.

— Adventure Travel

Azerbaijan with excursions to Georgia

Excerpt:

What to see, where to go

Contents list | Introduction | Getting to Azerbaijan | What to see, where to go | Exploring Baku's Old City | Mud volcanoes!

What to see, where to go

GEOGRAPHICAL OVERVIEW

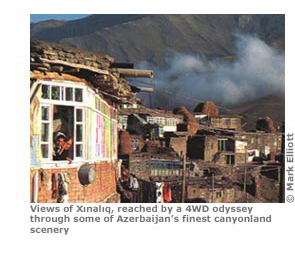

Baku has pretty much everything you would expect of a historic city with a million plus inhabitants. Its medieval walled old-city area is a UNESCO World Heritage site and the surrounding central area is delightfully cosmopolitan with attractive turn of the 20th-century buildings. The Absheron peninsula (p143) lacks scenic appeal but offers beaches and assorted curiosities (castles, religious sites and fire phenomena) plus a fascinating array of cultural discoveries: superstitious practices jarringly co-exist with Islam here in the nation’s most self-conscious pious Muslim communities. Also within day-trip range of Baku are the world-renowned Qobustan petroglyphs (p140) and some of the most delightful mud volcanoes (p142) anywhere. North of Baku the wildly colourful geology of the ‘Candy Cane’ mountains (p161) and the quaint twin towns of Quba and Krasnaya Sloboda (pp172-6) can be visited en route to one of numerous woodland getaway resorts but harder to reach in the dramatic mountains is a fabulous patchwork of canyons and timeless villages of which Xınalıq (p181) and Laza (p189) are the most spectacular.

The Shamakha–Shäki route (pp192-239) skirting just south of the High Caucasus foothills gives a fabulous snapshot of Azerbaijan’s extraordinary diversity with desert, farmland, forests and high mountains all within a few hours’ drive. Lahıc makes a great side trip and Shäki’s palaces and caravanserai hotel make it Azerbaijan’s foremost provincial attraction. This route is the recommended way to head for Georgia.

Central Azerbaijan (pp240-278) offers much less in the way of scenery and many of its historic sites are underwhelming, though if you can make it to Lake Göy Göl (unlikely, see p263) the scenery makes up for it all. Beautiful but Armenian-occupied Nagorno Karabagh (p275) is still tragically out of bounds to visits from the rest of Azerbaijan.

The south (pp279-303) is lushly fertile with thick woodlands and delightful hidden teahouses in the charmingly peaceful Talysh mountain foothills. The disconnected Nakhchivan enclave (pp304-316) has several important historical monuments scattered across a dramatically rocky semi-desert landscape but due to the closed borders with Armenia you’ll have to fly (or drive via Iran or Georgia/Turkey) to get there.

LAND OF FIRE

Tourists and Zoroastrians alike are fascinated to see fire emerging spontaneously from the earth. The classic ‘ateshgah’ is the Suraxanı Fire Temple (p154) but some visitors prefer the spooky naturalism of Yanar Da? (pp155-6). The small natural ateshgah beyond Xınalıq (p182) is in a fabulously scenic amphitheatre of mountains. There are Yanar Bulaq burning springs at Archivan (p302) and near Qäsämänlı (p272) while west of Masallı there’s a remarkable section of river that catches fire when lit (pp288-9).

BEACHES

Azerbaijan isn’t a beach paradise. Still, Baku weekenders can cool off with a dip at Shix(ov) (p138) or on the north Absheron coast (p150, p159). Much harder to reach and virtually unknown are the narrow shell/sand beaches around Shurabad (p161), Xachmaz (p168) and Narimanabad (p292). There’s a fairly decent grey-sand beach at Astara (p302) though the town isn’t Azerbaijan’s most welcoming. In summer locals rush off en masse to Nabran (p169), Azerbaijan’s top seaside strip, but those with time and money prefer Turkey, Spain or Dubai.

MUD VOLCANOES (Palchik Volkane, J Gryazevye Vulkan)

Like cows, mud volcanoes constantly fart flammable gasses. They also like throwing gobs of mud and streaming forth watery flows with a vigour that varies seasonally. This behaviour is gently amusing rather than life threatening. Unlike ‘normal’ volcanoes, mud volcanoes are cold and have multiple vents (gainarja) through which they exhale. These come in two types: gryphons (distinctive, abrupt conical nozzles) and salses (bubbling watery pools). Each has its own rather lovable character and when gathered in groups they almost appear to converse. Though not unique, Azerbaijan has more of these odd ‘creatures’ than any other country in the world, around 300 groups on land plus hundreds more offshore where they sometimes rise to form islands in the shallow coastal waters.

Where to see them?

Classic giants such as Turaguy are impressive from a distance but smaller volcano hills often have a better collection of active gryphons and salses. From Baku the most accessible group is right beside the road to Shamakha (see p193). Less dramatic but even nearer there are some extinct gryphons along the Baku bypass. However, the most interesting active groups are between Älät and Qobustan at ‘Clangerland’ (p142) and Bahar near Dashgil (see map p141) where a recent giant mud flow is particularly impressive. Deep in the desert between Ceyrankachmas and Pir Hussein are yet more.

POST-SOVIET CURIOSITIES

In its wake, the Soviet system left a legacy of appalling pollution and ecological mismanagement (especially on the Absheron Peninsula) which will take years and billions of manats for Azerbaijan to clear up. Stacks of junked vehicles, despoiled oilfields and satanic-ruined factories are not obvious tourist attractions. Yet perversely, some such places are so awesomely dreadful that they are compulsively photogenic. Seeking out the isolated last statues of Communist icons also appeals to certain tastes.

Oilfield landscapes

The greatest views of massed derricks were once between Bayil and Bibi Heybat but this ‘James Bond Oilfield’ (p104) is being reclaimed. For other remarkable vistas of antiquated nodding donkeys and gruesome-coloured run-off pools look down (west) from Ramana Castle (p153). Or climb Lök-batan’s blown-out mud volcano (p138) for fantastic all-encompassing views of oilfields, building yards and offshore installations. Assuming you can’t get to Neft Dashlari (p152) the next best thing is the network of roads on stilts heading miles out to sea south of Sangachal (p140) and best surveyed from the terrace of the Qobustan petroglyphs museum. For oil-field archaeologists the 1880s’ hand-dug well remnants south of Yanar Da? (pp155-6) are an incredible discovery – almost certainly unique anywhere in the world.

Other sad scenes Fascinatingly disturbing landscapes include the huge aluminium smelter and associated ‘red mess’ on the eastern edge of Gänjä, the vast quarry at Dashkäsän (p264), and the vast rusting post-industrial nightmare that was once Sumgayit’s chemical works (p157) – wow! Depending on the wind direction, the billowing chimneys of Qaradagh cement works can produce a peculiar, photogenic grey curtain or simply smother everything in a filthy dust cloud (p139). Moving for altogether different reasons are the Shafaq graveyard (p252), post-holocaust Asha?ı A?cakänd (p253) and the village of Narimanabad which seems idyllic until you walk down Narimanov St (p292).

Lenin

On 20th Jan 1990 the Red Army massacred hundreds of innocent civilians in Baku. Spontaneously people began to discard their Communist Party membership cards as a sign of defiance to the perpetrators of the outrage. As the country became independent, Lenin statues disappeared from virtually every town square, village office and factory gate. But not quite all of them.

Vladimir Ilich still stands proudly near Puta (p139), there are two minuscule busts on the summit of Mt Shahda? and a brilliant giant Lenin in Yevlax, sawn in half (see photo C11 and p248).

For years locals couldn’t imagine the attraction of the old Soviet symbols. However, a certain comic-nostalgia is creeping in. There’s now a handful of places that sell Lenin heads (eg Baku ∂G4) plus a couple of cafés with Soviet nostalgia themes – the USSR in Baku (Tagiyev St) and the Retro at Amburan (p146).

In Georgia there’s still a big statue of Stalin in his home-town, Gori (pp344-5).

ARCHITECTURE

Thanks to the multitude of earthquakes and invasions, relatively little of Azerbaijan’s truly ancient architecture remains. The most notable medieval exceptions are Baku’s unique Maiden’s Tower and the Momine Khatun mausoleum tower in Nakhchivan.

Surviving buildings from the 12th to 19th centuries are predominantly religious, though several caravanserais (Baku, Shäki, Sangachal, A?dash), brick bath-houses, and many castle ruins (best at Chirax, Gädäbäy/Rustam Aliev, Perigala/Muxax) remain. There are khans’ palaces in Baku, Shäki and Nakhchivan.

Architectural styles

- Tomb tower design There are three main types: a polygonal cross-section with pointed polyhedral roof comes from ancient Hittite design and was also the most popular throughout eastern Turkey and Armenia. The best examples are at Häzrä (p211), Kalaxana (p202) and Göylar Da? (p202). Taller Persian-influenced polygonal or cylindrical towers are often decorated with blue majolica tiles, most impressively at Nakhchivan (p307), Qaraba?lar (p315) and Bärdä (pp248-50). Stubby cubic or cuboidal bases with a dome are taken from stylized miniaturizations of local mosque designs and are relatively common.

- Mosque design The most visually appealing old mosques are in Baku, Gänjä (Imamzade shrine), Ordubad and Bärdä, with several more in Shäki. Traditional designs vary considerably from area to area. Shamakha’s mosque (p197), misleadingly dubbed the ‘second oldest in the Caucasus’, has a unique temple-like appearance. A flat-roofed stone cube with a simple central dome is particularly common on the Absheron Peninsula, while a simple wooden-house-style box with a timber-pillared entrance area is more common in the foothills above Ismayıllı (Lahıc, Damırchı). Around Zaqatala, large multi-arched structures are favoured (Tala, Muxax, Balakän) while in the far south several follow a quite distinct style with a small central chimney-like turret and arched stained-glass windows (Pensar, Qumbashi, Alasha). Baku’s old stone mosques are relatively ornate by Azeri standards.

Many square-plan Lezghian village mosques (Qächräsh, Alpan, Qusar Laza etc) have spaceship metallic towers and steep-pitched corrugated roofs belying their often considerable age. A few dramatic Turkish-style new stone mosques with big dome and associated minarets have been built in recent years, notably in Qusar, Zaqatala, Mingächevir, Nakhchivan and Nardaran.

- Mosque and tomb ornamentation Pre-14th-century builders mostly used geometrical patterns and stalactite vaulting. Where tiled, the predominance of blue decoration was due to the durability of available dye stuffs. More often carved or smoothed stone was left bare. A more recent fashion for shrine interiors are the dazzling mosaics of mirrored mini tiles like the Imamzadehs of neighbouring Iran.

- Hamams Bath-houses (hamams) were a great leap forward for public sanitation, especially in desert towns where there was little fresh water or firewood to heat it. Usually multi-domed, brick-built low buildings, many century-old examples are still functioning (Baku, A?dash, Qazax). Indeed the idea of a hamam party as a sort of Azeri stag-night is re-emerging and some classic historic bath-houses have been suitably gentrified to fill the demand (eg Baku’s Tazabäy hamam, p102, p101 πM8). Even ruined hamams remain interesting architectural monuments, as with Quba’s strange single-domed bee-hive design, p172.

- Caravanserais Caravanserais were the truckers’ motels of the Silk Route: a place to sleep, eat and park the camel. While each design has its own peculiarities, the essential feature is a series of small basic rooms around a lockable courtyard, all very solidly built to keep out thieves and bandits.

While the term now seems deeply antiquated, in fact caravanserais were still being built until the beginning of the 20th century.

- City gates When city walls were demolished in the 19th century, there remained little need for the traditional town gates. However, a recent fashion has led several provincial towns to erect imposing new gateways at their nominal city limits, often several kilometres from the town centre.

Oil-boom architecture

Styles started to change radically from the latter half of the 19th century. The initial division of oil-prospecting land into very small, affordable plots meant that even the poorest peasant or worker had a lottery chance of digging out a ‘gusher’.

Dozens of illiterate overnight millionaires spent the years between 1880 and WWI vying to outdo one another with displays of new-found opulence and ‘good taste’ with typical nouveau-riche zeal. Teams of architects were brought to Baku from Europe and Russia, while local architects and the oil magnates themselves toured Europe looking for designs and motifs which caught their fancy.

The resulting ‘oil-boom style’ is thus an unabashed mélange with an immediate appeal to anyone except po-faced architectural purists. Though neglected and sub-divided during the Soviet era, the basic fabric of most of these mansions survives.

20th- and 21st-century architecture

Inspirational guide Fuad Akhundov succinctly sums up the three main phases of 20th-century design:

1900-1915 Impressive

1920-1955 Oppressive

1955-1990 Depressive

He sees the cycle reversing now. Although there’s no new Stalin trying to daunt people with massive stone edifices as in the ‘40s and ‘50s, the almost endless growth of independence-era tower blocks do indeed seem to characterize a new oppressiveness – of rich over poor. But if extraordinary new plans are ever built, by 2020 Baku might be really architecturally impressive – assuming you like sci-fi glass grandeur (see ‘Baku – The New Dubai?’ box, p78).

The original oppressive phase was not only a political gesture but a real need to provide decent housing for some 10,000 families working in appalling conditions in the Absheron oilfields. Thus 380 apartment blocks were rushed to completion between 1925 and 1929. Initially apartment design tried to incorporate a few traditional features of local architecture such as pointed arched entrances, windows on wooden frames in 5x7-pane Shäbäkä patterns and, most practically, steps up to the doors to prevent dust collecting.

The remarkable post-WWII construction boom and the return to high-quality stone buildings with a surprising level of carved detail was possible in large part to the free labour of relatively skilled German prisoners of war who, in a little-known postscript to WWII, were not allowed to return till 1949-50 or even 1951. They were also put to work on the construction of railways.

MUSEUMS

Except in Baku, Azerbaijan has really only three types of museum, all with predictable format and content that, after a couple of visits, you’ll start to find cosily familiar (or crashingly monotonous). Fortunately few charge entry fees so there’s no need to fear stepping inside except for the embarrassment of waking up the slumbering attendants. Even if you don’t understand the language, you may be treated to a guided tour in Russian or Azeri if only because you’re the first visitor that week. There’s also the comical formality of signing the guest book: somehow visitors manage to fill acres of paper with their reflections. Occasionally guest books started in the 1970s have not yet been filled up and the communist-era entries can make intriguing reading as you’ll see at the Narimanov Apartment (p87) in Baku.

House museums

House museums are the mothballed homes of the great and the good and filled with their personal effects. While fascinating for fans of the individual concerned, such places are rarely a big draw for the average foreign tourist except perhaps for giving a taste of Soviet-era living conditions. The most compulsive such museum is Stalin’s father’s hovel in Gori (pp344-5), Georgia.

Historical (aka ‘Local Studies’) museums

Almost every mid-sized town and provincial capital has one, often situated in a building of local historic importance. Displays will almost inevitably start with some neolithic spearheads, a papier-maché tableau of cavemen and a tatty troop of stuffed animals. Then there’ll be a very cursory blast through 7000 years of history depicted in one or two rooms with a few copper pots (see diagram p208), carpets and old banknotes. This will be followed by a room dedicated to 20th-century horrors: WW2 (‘Great Patriotic War’), 20 January 1990, the Hojali massacre, and Karabagh with martyrs’ photos and medals.

The most interesting part of such museums is usually the fading photo-board depicting local scenes of architectural or archaeological interest. Sadly, the wardens who trail behind you like vultures don’t always know exactly where to find half the sites depicted. Instead you’re likely to be hurried on to give due honour to the last room which is almost inevitably filled with books by Heydar Aliyev.

Heydar Aliyev museums

Since his death in 2003, the Heydar personality cult has gone into overdrive. Today virtually every town has a Heydar Aliyev Park sporting a Heydar Aliyev statue and a swish new Heydar Aliyev museum. Curiously these museums’ mainly photographic exhibitions are often without labels but there’s usually an obliging guide at hand to talk you through if you don’t yet know the scenes by heart. You’ll soon start to recognize the same family photos from Heydar’s youth, his Moscow era and his handshakes with other world leaders including a pixie-faced Tony Blair. And you can bet there’ll be that classic ‘first oil’ photo of him smearing son (now president) Ilham’s face with crude oil. Heydar’s many books are lovingly encased and there’s usually one board of photos from the time that the great leader deigned to visit the town in question.

INTO THE MOUNTAINS

Azerbaijan’s hills and mountains offer unparalleled opportunities for summer off-road adventures by four-wheel drive vehicle, horse or foot. Alpine wild flowers will delight botanists while zoologists, ornithologists and hunters vie with one-another in the search for Caucasian black grouse, ceyran gazelles and tür mountain goats.

4WD adventures

Land was communal under the Soviet system and mostly remains unfenced. So, when the contours and terrain allow, you can go pretty much where you please on the wide sheep-grazed slopes. There’s a fine choice of routes around Altı A?ach, Chirax, Qonaqkänd, Söhub and Xınalıq, all approached from the Baku–Quba road. A fabulous variety of landscapes hide barely passable canyons and a web of challenging inter-village tracks on which you’ll stumble into timeless stone hamlets that rarely, if ever, see visitors.

The map on p70 shows a compilation of routes and average levels of difficulty (very subjective). On harder routes it’s best to go in a convoy of vehicles with a winch to pull each other out of muddy sections. After rain and especially as the snows melt, the mountain tracks can be treacherously slippery. Take spare fuel and tyres.

Approached from the south, the same mountains are harder to penetrate so there is a lower wow-per-ouch factor. Nonetheless, there are some challenging excursions behind Lahıc and Pirguli and attempting to find the route between the two (via Damirchi) is something of an offroader’s holy grail. The Talysh mountains in the far south offer some interesting possibilities too, but with a greater population density, more arable agriculture, wetter conditions and fewer dramatic peaks to discover it is something of a secondary choice. The Allar (p291) and Sım (p302) trips are interesting but punishingly tough.

In the lesser Caucasus there are some exciting routes south of Gänjä (Todan), Dashkasan (Mt Qoshqar) and Gädäbäy (via Rustam Aliev) but proximity to the ceasefire line reduces one’s options at present.

In the north-west a 4WD is handy to reach the forgotten Albanian churches in mountain villages such as Läkit and Bideyiz. These are a series of out and back trips, however, and even the toughest vehicles will struggle to ascend the upper river valleys where slopes are too steep and tree cover too thick for much off-roading.

Hiking

The off-roading areas mentioned above are perfect for hiking, as are the high mountains of the north-west. On foot, or with a horse (p19), you can climb into some magical ridge-top scenery with relatively minimal effort. Free camping, particularly in the north-east, is relatively safe though keep away from flocks of sheep – the shepherd dogs are trained to be extremely fierce. There are a few wolves and bears in the forests of the north-west.

Laza (p189), Kish (p227), Ilisu (p231), Vändam (p212), Lahıc (p206) and Car (p236) all make excellent bases for day hikes into the very best scenery and have handy places to stay. Xınalıq (p181) is probably best of all and makes a great starting point for longer hikes as guides and horses are comparatively easy to arrange there. Mondigar, Qalacık, Durja and Xoshbulaq are other tempting potential trailheads if you have a tent or a local friend to put you up.

Mountain biking

There’s lots of scope for off-road biking and Azerbaijan’s minor roads are generally very quiet (if often very bumpy). The Quba–Baku, Qazax–Älät, Baku–Länkäran and Baku–A?su roads are dangerously busy but other routes including Qäbälä–Balakän are pleasant for longer distance pedalling. Don’t expect to find many spares in Azerbaijan, though you might be able to get help at the Cycling Club beside the Velotrek Hotel in Baku. There’s also an active expat mountain bike club which organizes weekend rides and has put together some great off-road route suggestions, see www.baku bicycleclub.com.

Climbing and mountaineering

Baku rock climbers practise on a cliff near Bilgah/Amburan on the Absheron and occasionally venture to (holy) Besh Barmaq (p163) which makes for curious culture clashes. Baltagaya and Qizilqaya (between Xınalıq and north Laza) have spectacular mountain-top cliffs that offer particularly exciting climbing possibilities. In winter a frozen waterfall on Shahda? makes an interesting ice-climb when access allows.

If you want to climb any of the highest mountains, a guide is pretty much essential. In Baku you could approach the Extreme Sports Federation (91 Neftchilar, Baku, tel 012-437 3129, : www.fairex.az) or Baku’s Alpinist Klub (c/o Salydan, mob tel 050 320 9936). Various travel agencies can also arrange guides. Informal guides are also possible to find in Laza if you have all your own equipment.

Three of the big four Azeri mountains (Tufan, Bazardüzü, Shahda?) are approached by walking up the valley from Laza (Qusari Laza, p189) or by driving the extremely rough river-bed route by 4WD via Xınalıq to the very foot of Shahda? (see p185).

The fourth great mountain of Azerbaijan is 3629m Babada?. Somewhat away from the group described above, it can be approached from the north by following the Qarachay river south from Rük (p178), or from the south via Sumagalle/Istisu (tough) or Lahıc/Zarat Baba following a rough pilgrims’ trail. On the top, prayer ribbons and cairns mark Häzrät Baba pir, honouring a mysterious Albanian-era holy man who climbed the mountain and then disappeared, advancing directly to heaven without passing ‘Go’

Azerbaijan with excursions to Georgia

Excerpts:

- Contents list

- Introduction

- Getting to Azerbaijan

- What to see, where to go

- Exploring Baku's Old City

- Mud volcanoes!

Latest tweets