I've said it before and I'll say it again, Trailblazer guides take some beating.

— Adventure Travel

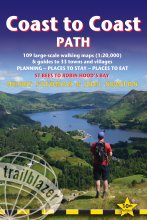

Coast to Coast Path: St Bees to Robin Hood's Bay

Excerpt:

About the Coast to Coast path

Contents | Introduction | About the Coast to Coast path | Practical information for the walker | Itineraries | Using this guide | Sample route guide: St Bees to Ennerdale Bridge

Wainwright’s Coast to Coast path

The Coast to Coast path owes its existence to one man: Alfred Wainwright. It was in 1972 that Wainwright, already renowned for his exquisitely illustrated guides to walking in the Lake District, finally completed a trek across the width of England along a path of his own devising. It was an idea that he had been kicking around for a time: to cross his native land on a route that, as far as he was aware, would ‘commit no offence against privacy nor trample on the sensitive corns of landowners and tenants’. The result of his walk, a guidebook, was originally printed by his long-time publishers, The Westmoreland Gazette, the following year. It proved hugely successful. Indeed, a full twenty years after the book was first published, a television series of the trail was also made in which Wainwright himself starred, allowing a wider public to witness firsthand his wry, abrupt, earthy charm.

Wainwright reminds people in his book that his is just one of many such trails across England that could be devised, and since Wainwright’s book other Coast to Coast walks have indeed been established. Yet it is still his trail that is by far and away the most popular, and in order to distinguish it from the others, it is now commonly known as Wainwright’s Coast to Coast path.

The route has been amended slightly since 1973 mostly because, though careful to try to use only public rights of way, in a few places Wainwright’s original trail actually intruded upon private land. Indeed, even today the trail does in places cross private territory and it’s only due to the largesse of the landowners that the path has remained near-enough unchanged throughout its course.

Though the trail passes through three national parks, crosses the Pennine Way and at times joins with both the Lyke Wake Walk and the Cleveland Way, it’s not itself one of the 15 national trails in the UK, nor is it likely to become one anytime soon. What is certain is that despite this lack of official support, the Coast to Coast has become one of the most popular of Britain’s long-distance paths, with estimates of up to 10,000 people attempting it annually.

How difficult is the Coast to Coast path?

Undertaken in one go the Coast to Coast path is a long, tough walk. Despite the presence of some fairly steep gradients, every mile is ‘walkable’ and no mountaineering or climbing skills are necessary. All you need is some suitable clothing, a bit of money, a backpack full of determination and a half-decent pair of calf muscles. In the 190-odd miles from seashore to seashore you’ll have ascended and of course descended the equivalent height of Mount Everest.

That said, the most common complaint we’ve received about this book, particularly from North American readers, is that it doesn’t emphasise how tough it can be. So let us be clear: the Coast to Coast is a tough trek, particularly if undertaken in one go. Ramblers describe it as ‘challenging’ and they’re not wrong. When walkers begin to appreciate just how tough the walk can be, what they’re really discovering is the reality of covering a daily average of just over 14 miles or 23km, day after day, for two weeks, in fair weather or foul and while nursing a varying array of aches and pains. After all, how often do any of us walk 14 miles in a day, let alone continuously for two weeks?

The Lake District, in particular, contains many steep sections that will test you to the limit; however, there are also plenty of genteel tearooms and accommodation options in this section should you prefer to break your days into easier sections.

The topography of the eastern section is less extreme, though the number of places with accommodation drops too, and for a couple of days you may find yourself walking 15 miles or more in order to reach a town or village on the trail that has somewhere to stay.

Regarding safety, there are few places on the regular trail where it would be possible to fall from a great height, save perhaps for the cliff walks that book-end the walk. On some of the high-level Lakeland alternatives (see p123 and p133), however, there is a chance of being blown off a ridge. In 2009 a walker suffered this fate and broke his ankle, as did the rescuer who came in a helicopter, though sustaining such a serious injury by being blown over is highly unusual. The greatest danger to trekkers is, perhaps, the likelihood of losing the way, particularly in the Lake District with its greater chance of poor visibility, bad weather and a distinct lack of signposting. A compass and knowing how to use it is vital, as is appropriate clothing for inclement weather and most importantly of all, a pair of boots which you ease on each morning with a smile not a grimace.

Not pushing yourself too hard is important, too, as this leads to fatigue with all its inherent dangers, not least poor decision making. In case all this deters you from the walk bear in mind that in 2009 a 71-year-old finished the walk for the fifth time, and a 7-year-old girl once completed the walk with her father – and they all managed it in 13 days! At the same time young men with all the right kit and a previous crossing under their belt were finished after storming across to Shap in three days.

How long do you need?

We’ve heard about an athlete who completed the entire Coast to Coast path in just 37 hours and a walker who managed it in eight days. We also know somebody who did it in ten and another guy who did four four-day stages over four years. Continuously or over several visits, for most people, the Coast to Coast trail takes a minimum of 14 walking days, in other words an average distance of just over 14 miles (23km) a day. Indeed, even with a fortnight in which to complete the trail, many people still find it tough going, and it doesn’t really allow you time to look around places such as Grasmere or Richmond which can deserve a day in themselves. So, if you can afford to build a couple of rest days into your itinerary or even break it up into shorter stages over several weeks, you’ll be very glad you did.

Of course, if you’re fit there’s no reason why you can’t go a little faster if that’s what you want to do, though you’ll end up having a different sort of trek to most of the other people on the route. For where theirs is a fairly relaxing holiday, yours will be more of a sport as you try to reach the finishing line on schedule. There’s nothing wrong with this approach, though you obviously won’t see as much as those who take their time; chacun à son goût, as the French probably say. However, what you mustn’t do is try to push yourself beyond your body’s ability; such punishing challenges often end prematurely in exhaustion, injury or, at the absolute least, an unpleasant time.

When deciding how long to allow for their trek, those intending to camp and carry their own luggage shouldn’t underestimate just how much a heavy pack can wear you down. On pp34-5 there are some suggested itineraries covering different walking speeds. If you’ve only got a few days, don’t try to walk it all; concentrate, instead, on one area such as the Lakes or North York Moors. You can always come back and attempt the rest of the walk another time.

Coast to Coast Path: St Bees to Robin Hood's Bay

Excerpts:

- Contents

- Introduction

- About the Coast to Coast path

- Practical information for the walker

- Itineraries

- Using this guide

- Sample route guide: St Bees to Ennerdale Bridge

Price: £13.99 buy online now…

Latest tweets