Engagingly written — all the guides from this stable are first class

— Traveller

Dolomites Trekking

Excerpt:

Introduction

Contents | Introduction | Route options and when to go | With a group or independently? | Sample route guide | Minimum impact trekking

‘I crossed many passes, I found many unknown sites of great beauty, I discovered many of those wild peaks. They attracted me with their apparent inaccessibility, and appeared even more desireable (sic)’.

Paul Grohmann, conqueror of the Dolomites’ highest peak, the Marmolada.

In 1789, the celebrated mineralogist Deodonn� Sylvian Guy Tancr�de de Gratet de Dolomieu (or Deodat to his friends) embarked on a journey to Rome from his native France. By all accounts, the trip wasn't particularly eventful, certainly by the standards of the eighteenth

century. Nevertheless, it was this journey that led Dolomieu to discover the mineral that today bears his name; a discovery that not only brought him both fame and fortune during his lifetime but which would also, long after his death, result in an entire mountain range being named after him. For while

passing through a valley in what was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Dolomieu's attention was caught by some unusually vivid rocks and

stones that lay in abundance on the ground by the side of the road. Unable to identify the rocks, Dolomieu paused to collect some samples and, on

his return to France, ran a series of tests that proved that these rocks were composed of calcium magnesium carbonate, a previously unidentified

mineral.

In honour of Dolomieu's discovery, a few years later both the mineral and the rock were named after him. Then in 1864, a full 95 years after his journey, two itinerant English geologists, J Gilbert and GC Churchill, published The Dolomite Mountains, an account of their explorations in a mountainous region that had previously been known by a whole series of names, including the Venetian Alps and, more poetically (if a little less accurately), the Monte Pallidi ('Pale Mountains'). The book's title caught on and ever since this small yet sublimely beautiful range has been known as the Dolomite Mountains, or simply, the Dolomites. (Incidentally, there's a certain irony in the fact that, though the mineral that he identified exists in abundance in these mountains, and though the entire range is named after him, Dolomieu himself never actually visited the Dolomites, his rock samples having been taken from the Valle Isarco to the north-west of the range.)

Gilbert and Churchill's explorations, along with those of other British pioneers such as John Ball, Amelia Edwards and the Austrian climber Paul Grohmann, paved the way for the tourist industry of the late 1800s. Before the century was over, mountaineers, skiers, trekkers and thrill-seekers from all corners of Europe were flocking to this small mountainous part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Few would have been disappointed by what they found. The Dolomites may not be the largest range in Europe, nor are its mountains particularly massive when compared to the giants of neighbouring Austria and Switzerland. But what these mountains lack in scale they more than make up for in both beauty and diversity. It is in the Dolomites that you find some of nature's boldest designs: sheer pinnacles of pink and grey soaring above grumbling glaciers and windswept, karstic plateaux. Here, too, you can witness the natural phenomenon of Alpenglow – or enrosadira as it's known in the local Ladin language – where the mountains seem to glow a vivid pink and orange in the late afternoon sun. While down in the valleys that separate these massifs, you'll come across any number of enchanting little villages, each huddled around over-sized mediaeval churches.

The Dolomites is also the region where the neatly manicured gardens and lovingly-tended window boxes of the Southern Tyrol meet the Renaissance-inspired glories of Italian architecture; sandwiched between these two cultures we find the Ladin people, one of the smallest ethnic minorities in Europe who, despite a history in which they have been the subjects of one vainglorious empire after another, have managed to retain their own language and identity. Their folktales, too, have received widespread recognition, which in turn have helped to perpetuate the notion that the Dolomites is the haunt of a whole host of sage old wizards, greedy goblins, despotic mountain kings and innumerable lovelorn princesses. It is a notion that the mountains’ wild and primordial landscape, its lonely peaks and deep, dark forests, does little to dispel.

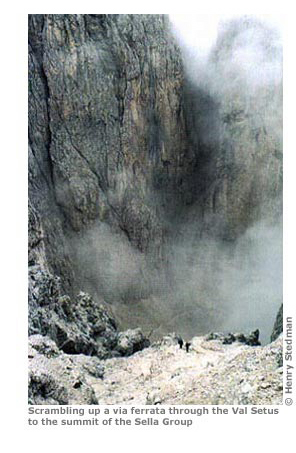

Thankfully, the mountains’ charms are not just for the adventurous and intrepid. As well as an extensive network of well-maintained footpaths, the Dolomites are renowned for their vie ferrate, steep and/or exposed trails where assistance – in the form of iron cables, metal rungs and ladders – has been provided along parts of the trail. This allows those with little or no climbing skills a chance to see the kind of awesome panoramas that were once the sole preserve of accomplished climbers.

I give the last word of this introduction, as I gave the first, to the 19th-century Austrian climber Paul Grohmann and hope that when you, too, feast your eyes upon these extraordinary mountains, you'll experience the same sense of awe and wonder as he did over a century ago:

'When from the peaks and heights of the Tauri Range, which I had explored up to that moment, I cast my gaze southwards, I saw a brand new world of beautifully-shaped mountains which even the best book could not describe in detail. It was an alpine world still covered in mystery. I decided to go to the Dolomites and work there.'

Latest tweets