Trailblazer Guides are produced by people who know exactly what information is needed - not just to get from A to B but to be entertaining as well as informative.

— The Great Outdoors

Kilimanjaro - The trekking guide to Africa's highest mountain

Excerpt:

Sample route: Marangu

Contents List | Introduction | Planning your trip | Minimum impact trekking | Sample route: Marangu | On the Trail

The Marangu Route

Because this trail is popularly called the ‘Tourist Trail’ or ‘Coca Cola trail’, some trekkers are misled into thinking this 5- or 6-day climb to the summit is simply a walk in the (national) park. But remember that a greater proportion of people fail on this route than on any other. True, this may have something to do with the fact that Marangu’s reputation for being ‘easy’ attracts the more inexperienced, out-of-condition trekkers who don’t realize that they are embarking on a 36.55km uphill walk, followed immediately by a 36.55km knee-jarring descent. But it shouldn’t take much to realize that Marangu is not much easier than any other trail: with the Machame Route, for example, you start at 1811m and aim for the summit at 5895m. On Marangu, you start just a little higher at 1905m and have the same goal, so simple logic should tell you that it can’t be that much easier. Indeed, the fact that this route is often completed in 5-6 days as opposed to the 6-7 days it takes to complete Machame would suggest that this route is actually more arduous – and gives you some idea of why more people fail on this trail than on the so-called ‘Whiskey Route’.

The main reason why people say that Marangu is easier is because it is the only route where you sleep in huts rather than under canvas. The accommodation in these huts should be booked in advance by your tour company, who have to pay a deposit per person per night to KINAPA in order to secure it. To cover this, the tour agencies will probably ask you to pay them some money in advance too. This deposit is refundable or can be moved to secure huts on other dates, providing you give KINAPA (and your agency) at least seven days’ notice.

(Bear in mind if you’re booking with a Tanzanian agency for a trek the next day, you should ask your agency to show you a receipt confirming they have paid a deposit for your accommodation on the trek. Otherwise, you may find yourself being turned away at Marangu Gate at the start of the trek because your company didn’t book your accommodation and there’s no room.) Incidentally, there are currently 84 spaces at Mandara Huts, 160 at Horombo – the extra beds are necessary because this hut is also used by those descending from Kibo – and 60 at Kibo.

If any one of those is already booked to capacity on the night you wish to stay there, you won’t be allowed to start your trek and will have to change your dates.

The fact that you do sleep in huts makes little difference to what you need to pack for the trek, for sleeping bags are still required (the huts have pillows and mattresses but that’s all) though you can dispense with a ground mat for this route. Regarding the sleeping situation, it does help if you can get to the huts early each day to grab the better beds. This doesn’t mean you should deliberately hurry to the huts, which will reduce your enjoyment of the trek and increase the possibility of AMS. But do try to start early each morning: that way you can avoid the crowds, beat them to the better beds, and possibly improve your chances of seeing some of Kili’s wildlife too.

In terms of duration, the Marangu Route is one of the shorter trails, taking just five days for both the ascent and descent. Many people, however, opt to take an extra day to acclimatize at Horombo Huts, using that day to visit the Mawenzi Huts at 4535m. From a safety point of view this is entirely sensible and aesthetically such a plan cannot be argued with either, for the views from the path to the huts across the Saddle to Kibo truly take your breath away – assuming you have some left to be taken away after all that climbing.

One aspect of the Marangu Route that could be seen by some as a drawback is that it is the only one where you ascend and descend via the same path. However, there are a couple of arguments to counter this perception: firstly, between Horombo and Kibo Huts there are two paths and it shouldn’t take too much to persuade your guide to use one trail on the ascent and a different one on the way down; and there’s a Nature Trail alternative on the descent from Mandara Huts to the gate as well. Both of these are described in the book on p335 and p336 respectively. Secondly, we think that the walk back down the Marangu Route is one of the most pleasurable parts of the entire trek, with the gradients more gentle than on other descents and splendid views over the shoulder. Furthermore, it offers you the chance to greet the crowds of sweating, red-faced unfortunates heading the other way with the smug expression of one for whom physical pain is now a thing of the past and whose immediate future is filled with warm showers and cold beers.

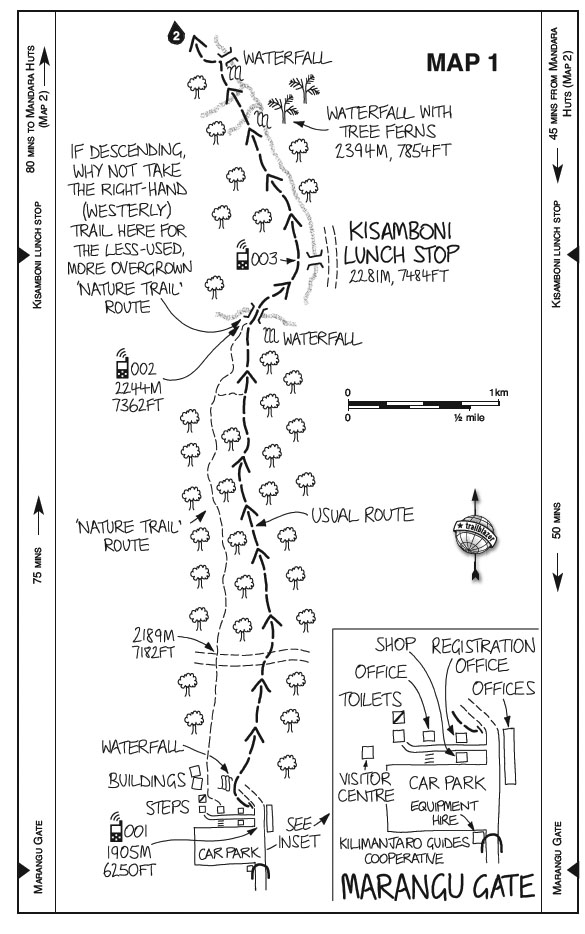

STAGE 1: MARANGU GATE TO MANDARA HUTS [MAP 1, p255; MAP 2, p257]

Distance: 8.3km (8.75km if taking the Nature Trail); altitude gained: 818m

The woods are lovely, dark & deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep. Robert Frost as seen on a signwriter’s wall in Moshi

As the headquarters of KINAPA (Kilimanjaro National Park), you might expect Marangu Gate (altitude 1905m/ 6256ft) to have the best facilities of all the gates and it doesn’t disappoint. Not only does the gate have the usual registration office but there’s also a picnic area, a smart new toilet block and a shop that has a good collection of books and souvenirs. There’s also a small booth run by Kilimanjaro Guides Cooperative by the entrance to the car park where you can hire any equipment you may have forgotten to bring along, from essentials such as hats and fleeces, sleeping bags and water bottles to camping stuff that you almost certainly won’t need on the trail such as stoves and so forth, which should be provided by your agency. (Incidentally, the authorities have even bigger plans for this gate, with blueprints for a whole new visitor centre already drawn up, including a conference hall, internet café and a museum dedicated to the mountain.)

Having gone through the laborious business of registering (a process that usually takes at least an hour, though it can be quicker if you manage to get here before the large tour groups arrive), you begin your trek by following the trekkers’ path which heads left off the road (which is now used solely by porters). You may still find the odd eucalyptus tree around the gate, one of the few non-native plants on the mountain. They were introduced, according to the version I’ve heard, by the first chief park warden of Kilimanjaro, a man who married a relative of Idi Amin – the former despot of Uganda later shooting him in an argument, so the story goes. As an ‘alien’ species and one that consumes a lot of water, the eucalyptus trees are slowly being eradicated by the authorities from the national park itself. (It has to be a gradual process, however: look through the trees to your right just after you start out and you’ll see a big open area – the ugly result of eradicating the trees too quickly.)

This first day’s walk is a very pleasant one of just over 8km and though the route is uphill for virtually the entire time, there are enough distractions in the forest to take your mind off the exertion, from the occasional troop of blue monkeys to the vivid red Impatiens kilimanjari, a small flower that has almost become the emblem of Kilimanjaro. The path soon veers towards and then follows the course of a mountain stream; sometimes through the increasingly impenetrable vegetation to your right you can glimpse the occasional small waterfall.

After about 1? hours a wooden bridge leads off the trail over this stream to the picnic tables at Kisamboni and a reunion with the 4WD porters’ trail. This is the halfway point of the first stage and in all probability it is here that you will be served lunch.

... ferns and heaths were plentiful, the last-named preponderating as we got higher up. At a height of 6,300 feet, however, all these were merged in the primaeval forest, in which old patriarchs with knotted stunted forms stood closely together, many of them worsted in the perpetual struggle with the encroachments of the parasitical growths of almost fabulous strength and size, which enfolded trunks and branches alike in their fatal embrace, crippling the giants themselves and squeezing to death the mosses, lichens, and ferns which had clothed their nakedness. Everything living seemed doomed to fall prey to them, but they in their turn bore their own heavy burden of parasites; creepers, from a yard to two yards long, hanging down in garlands and festoons, or forming one thick veil shrouding whole clumps of trees. Wherever a little space had been left amongst the many fallen and decaying trunks, the ground was covered with a luxurious vegetation, including many varieties of herbaceous plants with bright coloured flowers, orchids, and the modest violet peeping out amongst them, whilst more numerous than all were different lycopods and sword-shaped ferns. Lieutenant Ludwig von Höhnel Discovery by Count Teleki of Lakes Rudolf and Stefanie (1894)

Returning to the trail and turning right, you continue climbing north for 30 minutes to another bridge, again leading off to the right of the trail; your path, however, heads off to the left, directly away from the bridge. The trail is a little steeper now as you wind your way through the forest. It is a very pretty part of the walk, with varieties of Impatiens and, draped amongst the trees, the white-flowered Begonia meyeri-johannis edging the path; though by now you may be feeling a little too tired to enjoy it to its fullest.

Press on, and 15 minutes later yet another bridge appears which you do take. Like some sort of botanical border post, the bridge heralds the first appearance of the giant heathers (Erica excelsa) on the trail, with masses of bearded lichen liberally draped over them; though the forest reappears intermittently up to and beyond Maundi Crater it’s the spindly heathers and stumpy shrubs of the second vegetation zone, the alpine heath and moorland, that now dominate.

From this bridge, the first night’s accommodation, Mandara Huts (2723m), lies just 35 minutes away. If you have the energy, a quick 15-minute saunter to the parasitic cone known as Maundi Crater is worthwhile both for its views east over Kenya and north-west to Mawenzi and for the wild flowers and grasses growing on its slopes. On the way to the crater, look in the trees for the bands of semi-tame monkeys, both blue and colobus, that live here and are particularly active at dusk.

Incidentally, Mandara Huts are the only huts on the mountain to be named after a person rather than a place. Mandara was the fearsome chief of Moshi, a warrior whose skill and bravery on the battlefield was matched only by his stunning cupidity off it. Mandara once boasted that he had met every white man to visit Kilimanjaro, from Johannes Rebmann to Hans Meyer, and it’s a fair bet that all of them would have been required to present the chief with a huge array of presents brought from their own country. Failure to do so was not an option, for those who, in Mandara’s eye (he had only one, having lost the other in battle), were insufficiently generous in their gift-giving, put their lives in peril. The attack that led to the death of Charles New (see p113), for example, was said to have been orchestrated by Mandara after New had ‘insulted’ him by refusing to give the chief the watch from his waistcoat. Read any of the 19th-century accounts of Kilimanjaro and you’ll usually find plenty of pages devoted to this fascinating character – with few casting him in a favourable light.

Kilimanjaro - The trekking guide to Africa's highest mountain

Excerpts:

- Contents List

- Introduction

- Planning your trip

- Minimum impact trekking

- Sample route: Marangu

- On the Trail

Price: £17.99 buy online now…

Latest tweets