'These human-scale books, written and published by people who genuinely know and love their subject, are perfect for travel's post-pandemic recovery.'

— The Guardian, March 2021

Adventure Motorcycling Handbook

Excerpt:

Life on the road

Contents list | AMH history | Introduction | Planning | Choosing a motorcycle | Life on the road | Sample route outline (Peru and Bolivia) | Tales from the Saddle (sample)

Life on the road

The Big Day arrives and the Sky News chopper is buzzing the neighbourhood while colourful street-bunting flutters in the breeze. Or more likely, some friends and family are buzzing around and the fluttering is in your stomach because one thing’s fairly certain, you’ll be nervous. If you’ve had the time to prepare thoroughly and get everything sorted and packed, pat yourself on the back. Chances are though, like most mortals, you’ll have overlooked something, or will be dealing with a last-minute cock-up. This seems to be normal, another test thrown down from the gods of the overland. Expect it.

One great way of avoiding a last-minute panic is to pack the bike days before you leave, or gather everything you need in a safe space like a garage. Assembling all the gear, at this stage you’re not yet chewing your lip over an imminent departure, but instead have a few days to thoughtfully check the bike and tick off a checklist. There’ll still be eleventh-hour things to buy or do but, this way, should the handlebars come away in your hands there’ll be enough time to bolt them back on and still stay on schedule.

SHAKEDOWN TRIP

Many of us will have travelled abroad in one way or another before setting off on our big motorcycle adventure. For the rest with less experience, the best way of reducing the shock of hitting the road on the big one is to hit the road on a small one. A shakedown trip of a week or two to somewhere as far as you dare will be an invaluable dress rehearsal. When the real thing comes along it won’t feel so daunting, just another trip that’s a little bit further this time.

On a test run you’ll have a chance to refine your set up without unnecessary pressure. Some flaw may also manifest itself – a wobble or vibration, overheating, or that expensive jacket or helmet driving you nuts. Better to know this while there’s plenty of time to do something about it.

From western Europe, somewhere like Morocco, Turkey or even just eastern Europe can give an idea of what it’s like to be in a significantly foreign country on the edge of the overland zone. From North America it’s obviously going to be Mexico and Central America, while South Africans can roam far north into their continent, taking on progressively more challenging countries as they go. For those I’ve missed out, you get the picture.

A short test run or an organised tour (see p30) can be used to find out if you even like the idea of a long-haul trip of your own. You may acknowledge that a short trip is as much as you want to take on at this stage in your life. It’s nice to go camping on your well set-up bike for a couple of weeks, but hauling it all the way to Vladivostok or Ushuaia might be too much of a commitment. Again, it’s better to find all this out by wading out from the shallows rather than diving in at the deep end with a full backpack.

SETTING OFF

So here it is. You climb aboard, start the engine, heave the bike off the stand (don’t forget to flick it up!), clunk into first and wobble off down the road, utterly appalled at the weight of your rig. Once out on the open road you wind it up and allow some faint optimism to creep in to your multiplying anxieties as passing motorists glance at you with what you hope is envy.

Finally on the move after months if not years of preparation, the urge is to keep moving, especially if you’re heading out across a cold continent. Recognise this restlessness for what it is: an inability to relax for fear that something bad is going to happen. It’s all part of the acclimatisation process as your life takes on a whole new direction.

Once abroad, try to resist covering excessive mileages in the early days. Racing through unfamiliar countries with perplexing road signs and ‘wrong-side’ driving can lead to misjudgements. If an estimated three-quarters of all overlanders achieve hospitalisation through accidents, rather than commonly-dreaded diseases, hyena attacks or banditry, you can imagine what that figure is for motorcyclists. In many cases it happens early in the trip.

Then again, it may be your head that’s on the wrong side of the road, not your bike. It will be intensely galling, but if things don’t feel right or get off to a bad start and you have a chance to correct them, turn back. If you didn’t make a big splash no one need know. To help give yourself a good chance of not needing to do that, don’t make any crazy deadlines to quit work and catch a ferry the next morning, or plan to pick up a visa three countries away in less than a week. Instead, after a couple of days on the road make a conscious effort to park up somewhere warm and sunny or visit friends to give you a chance to catch your breath. Spread out for a while, tinker with the bike and just get used to being away from home but not up to your neck in it just yet. If you’re a bit shaky about the whole enterprise it can make a real difference to your mood. And especially when on your own, managing your moods is as important as keeping on the correct side of the road.

The shock of the new

Alone on your first big trip into foreign lands it’s normal to feel self conscious, intimidated, if not a little paranoid. This is because you’ve just ejected yourself from your comfort zone and are entering the thrill of an adventure. ‘Adventure travel’ has become tourism marketing jargon to distinguish trekking holidays from lying on a towel by a pool. But as far as this book’s concerned, an ‘adventure’ is what it always was: an activity with an uncertain and possibly dangerous outcome.

The less glamorous aspect of all this is the stress involved in dealing with strange people, languages, customs, places and food. Stress is usually what you’re looking to get away from, but it’s not necessarily a bad thing. Leaping into the air off the end of an elastic cord is stressful, so is standing up to give a speech or even taking a long-haul flight. To a certain extent it’s an emotional response to losing control, and can also be classified as excitement. Your senses are sharpened and your imagination is stimulated, but with this comes irritability and, initially, an exaggerated wariness of strange situations.

Having probably lived and worked in a secure environment for years, for better or for worse, setting off overland can be just about the most stressful and exciting thing you’ll have done for a long time. Fears of getting robbed, having a nasty accident, getting into trouble with the police or breaking down are all the more acute when everything you possess for the next few months is in arm’s reach. This situation is not improved by the way overseas news is presented in the media: one atrocity or tragedy after another. Who’d want to go to places like these?

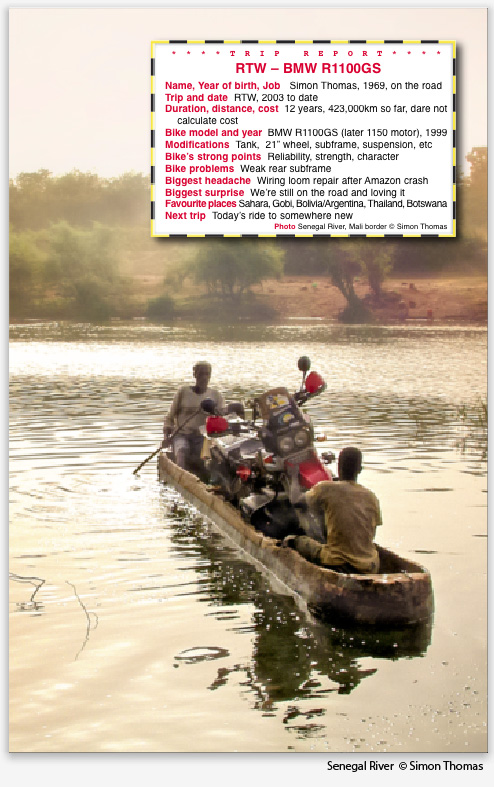

A crucial part of the acclimatisation to life on the road is learning to see the world for what it actually is: regular people getting on with their ordinary lives; just like back home. In the collection of over a thousand trip reports on the old AMH website the most common reply to the question: ‘Biggest surprise?’ was: ‘Friendliness of the people’. Many experienced overlanders come to recognise that when all’s said and done, it’s the good people they meet on their travels who count for more than the number of countries they visited or the gnarly roads they rode.

It’s hard to think so when you’ve spent months setting-up the bike while keeping tabs on the latest international crisis, but without expecting to teach the world to sing in perfect harmony, this is perhaps the single biggest lesson to learn from travelling. One of the most frustrating scenarios is when you realise you’ve been rude to someone who was only trying to help or be friendly. This can be understandable when you’ve been pestered for days by hustlers urging ‘Meester, psst. Hey Mister...’. Distinguishing genuine encounters from the others comes with experience, and very often the best encounters are found in rural areas where people are more ‘normal’. Those with a proclivity for hustling having migrated to the richer pickings in the cities and resorts.

It’s common to regard long motorcycle journeys as a series of hops from one congested, hassle-ridden city to another. Often it’s a bureaucratic requirement to do with acquiring visas (city strategies are on p126 and p172). But out in the country pressures are less acute and locals indifferent to you.

So make the most of roadside cafés for tea breaks, meals and rests. They’re great places to mix with local people without feeling like you’re on stage. The owners and customers will be regulars used to passing travellers and may well treat you like any other customer. Very often, that’s all you want.

RIDING ABROAD

Experienced motorcyclists will be well versed in the need to ride defensively, position themselves conspicuously and to anticipate the unexpected. Chances are, out in the AMZ the local driving standards won’t be what you’re used to back home. In these places very often the horn replaces the steering wheel or brakes. What’s missing is driver training and the respect we have for road rules and other road users (or the fear of the sanctions if we transgress).

Even if you’re riding with all the due care and attention you can muster, the ante is upped further by a possible absence of licensing, roadworthiness testing and motor insurance. You’ll be sharing roads with drunks, aggressive taxi drivers, amphetamine-fuelled truck drivers and ageing bangers which should have been melted down into cutlery years ago. Mixing with these unroadworthy crates are the imported, blacked-out limos of local criminals, businessmen and politicians (often all in the same car); stray domestic and wild animals and dozy pedestrians who were never taught to ‘look left, look right, and left again’. Throw in some more alcohol, a splash of Latino/ Arabic/Indian machismo, donkey carts, bad roads, unlit vehicles, unsigned diversions and unfinished bridges, plus some grossly overloaded vehicles, and you’ve arrived in the crazy world of riding in the AMZ where anything goes. All this can require an acute period of adjustment as you shudder past another pile of impossibly mangled wreckage being hosed off the road.

What’s needed is alertness mixed with a dose of assertiveness that doesn’t extend to aggression. This can be difficult to judge when, because you’re clearly a foreigner, you feel you’re being singled out by local young men who regard being overtaken by you as an insult akin to looking at their sister. A good way of rationalising this is to acknowledge that among the hundreds of drivers you pass in a day, you might generally encounter only one dickhead. Don’t always take tailgating personally: there’s a different concept of personal space out in the world (both on the road and in daily life). In fact, after a while this new uninhibited style of riding can be quite liberating; what counts is that all road users are on the same wavelength, and this now includes you.

Local driving customs

It’s said that in Mexico, and certainly in many other places, a vehicle in front that you wish to pass will signal on the off side if it’s safe to pass and to the near side (the kerb) if it’s not safe. This is the opposite of what’s done in Europe and North Africa, where a slow vehicle will indicate to the near side – ‘pulling over’ – that it’s safe to go for it. Misunderstanding these signals could be grave so don’t be rushed. Use your own judgement and visibility when performing such manoeuvres.

Back home flashing headlights usually means go ahead; it can also mean ‘watch out, speed trap/cops ahead’ when done to oncoming vehicles. In parts of North Africa flashing seems to ask ‘Have you seen me?’, except that just about every oncoming vehicle seems to require this affirmation on a flat and perfectly clear road. If you don’t flash back they’ll flash again urgently.

It can also be a message indicating ‘Hey dumbass, you’ve got your lights on in broad daylight!’, but it’s rarely pointing out something you don’t know, such as a condor is making a nest on your panniers.

The wrong side of the road

Although it’s less of a problem on a bike than a car, if you’ve never ridden in a country where they drive on the other side of the road it’s natural to be anxious about dealing with things like roundabouts. Riding fresh out of a foreign port, or crossing a border where driving sides change (as when crossing the northern borders of Pakistan, Angola or Kenya), you’re usually hyper-alert.

Roundabouts, or traffic circles to some, are a good example. They seem to be proliferating across the highways of the world as a traffic-signal free way of controlling traffic at a crossroads. In the UK you give way to traffic already on the roundabout, elsewhere you’re supposed to give priority to those entering the roundabout, but I bet I’m not the only one to have ridden in countries where they do it both ways. The answer is to slow down, make eye contact and go for it when you feel it’s safe.

In my experience you commonly get the side of the road wrong when either you’ve been on tracks with little traffic for days, or you pull off the highway in a rural area for a lazy lunch. On returning to the road, the lack of any roadside infrastructure or momentary passing traffic sees you instinctively do what you’ve done all your riding years: head off down what’s now the wrong side of the road. Luckily, such mistakes are usually made on quiet roads.

The other time you might blow it is when you’ve been riding for 20 hours non-stop, chomping Nescafé straight out of the jar. In a moment of frazzled panic you don’t know if right is wrong or left is right. This confusion can mess you up even if you’re in a country where they drive on the side you’re used to back home. As a Brit, for example, you assume anything ‘abroad’ must equate with driving on the right. Not if it’s Kenya or Thailand or crazy India, where left is right, right is wrong and might is right anyway. One trick that can help is visualising a memorable street scene back home. To a Brit, Australasian or southern African, most of the world is on the other side; remember the homely scene and get on the correct side, quick.

City strategies

Cairo, Quito, Dakar, Delhi; it’s a good thing they’re all so far apart. Like it or not your ride will be punctuated by visits to cities like these where dealing with congestion, noise and pollution comes on top of security issues and the expense of staying there. You need to go to these places for spares or repairs, to check email, get visas and, who knows, maybe even to stroll around the national museum or admire the Old Town at dusk.

If you have the choice, try to arrange visits to big cities on your terms. Above all, in a big, unfamiliar city it helps to know where you’re heading, as opposed to blundering around looking for a cheap hotel in the old quarter. If you’re having trouble finding the place you fixed on, hire a taxi driver or a kid on a moped to lead you there.

Some places like Islamabad and cities in East Africa have centrally located camping parks which are great places to meet other travellers. Many cities have guarded parking compounds, but as they’re usually a piece of waste ground so not necessarily good spots to leave a bike. Many small hotels have a courtyard or a storage lock-up where they’ll be happy to stash your bike, while others allow you to ride it right into reception overnight. If you have to leave it outside, a cheap bike cover helps reduce passing interest in the bike.

Adventure Motorcycling Handbook

Excerpts:

- Contents list

- AMH history

- Introduction

- Planning

- Choosing a motorcycle

- Life on the road

- Sample route outline (Peru and Bolivia)

- Tales from the Saddle (sample)

Price: £19.99 buy online now…

Latest tweets