Worth watching out for.

— John Cleare

Moroccan Atlas - the Trekking Guide

Excerpt:

Planning your trip

Contents | Introduction | Minimum impact trekking | Planning your trip | Marrakech | Using this guide | Sample trek: Toubkal circular trek | Moroccan Atlas Trekking Routes

With a group or on your own?

He must be a dog, he goes on foot. Arab proverb

In comparison with European ranges such as the Alps or the Pyrenees, tourism in the Atlas Mountains is relatively undeveloped, so trekkers seeking  solitude need not explore far beyond the more established routes; ‘established’ is a comparative word and indeed one meets few fellow trekkers even on the better-known routes. An exception is the Toubkal Circular Trek, although even here you may meet no more than a handful of trekkers once you have left behind the summit of Toubkal and the Aït Mizane Valley. There is a choice to be made, however: trekking with an organised group, with a guide, or completely alone.

solitude need not explore far beyond the more established routes; ‘established’ is a comparative word and indeed one meets few fellow trekkers even on the better-known routes. An exception is the Toubkal Circular Trek, although even here you may meet no more than a handful of trekkers once you have left behind the summit of Toubkal and the Aït Mizane Valley. There is a choice to be made, however: trekking with an organised group, with a guide, or completely alone.

INDEPENDENT TREKKING

Kipling said, ‘He travels the fastest who travels alone,’ but he had never navigated his way across the Atlas Mountains. It’s not easy. There are no route markers and the trails themselves can be very indistinct. All but the most competent trekkers and map readers well-versed in the use of a compass should seriously consider employing a local guide rather than travelling solo.

TREKKING WITH A GUIDE AND MULETEER

Guides

It is relatively inexpensive and easy to arrange to employ a guide and muleteer once you arrive at your chosen trailhead. An official guide will cost from about £25/US$37.50/300dh per day, while a muleteer, along with his mule, will cost around £10/US$15/120dh per day or perhaps £20/US$30/250dh if he agrees to double up as your cuisinier (cook; see p11). There are some very good reasons for using a guide:

- Safety A guide will help prevent you from getting lost and will be ready to help find a way out of the mountains in an emergency.

- Communication Atlas Berbers have only recently begun to welcome visitors to their previously hidden world. Few speak French and fewer still know English. A guide will act as an interpreter so that you can talk to local people; apart from the cultural insight that such an exchange might offer, this could be critical in an emergency.

- Understanding If you form a good relationship with your guide, which is likely over the course of a trek, you’ll benefit enormously from the chance this gives to learn more about Moroccan life and the land through which you pass.

- Enjoyment Finding your own way through the mountains will take some effort. Admittedly, it is this very challenge which appeals to some. However, if your guide is leading the way, you are free to concentrate on trekking rather than map-reading.

Morocco has a well-organised programme for training mountain guides. Would-be guides must pass a demanding three-day selection test before even being accepted on to the course. They are then given six months’ training at the Centre de Formation aux Métiers de Montagne (CFAMM) just outside Tabant before qualifying. As official guides usually live at trailheads, finding one is simple. They can be identified by the personalised guide de montagne card which bears their name and photograph as well as by the set of documents they are given upon qualification. You should always ask to see these before agreeing to employ a guide.

Although there are only about 400 officially trained guides in the country, it is important that you employ one rather than a ‘faux guide’ (unofficial guide). First and foremost, their profession is a proper one and they deserve to be taken seriously. They have undertaken a long and rigorous training which calls for respect. A guide who leads a trek into the mountains undertakes a big responsibility for your personal safety. Not only is a ‘faux guide’ untrained to cope with unforeseen circumstances, he works illegally and faces prison should you have an accident. He may be able to offer his services for a lower price than an official guide, but he is able to do this because he neither declares his earnings nor pays tax.

There are likely to be times when employment of a guide will bring its own difficulties. To minimise the chance of this, do not engage the first official guide you find simply because he is qualified. It is important to employ a guide with whom you can develop a friendly, working relationship. First, drink tea, talk together and try to gauge whether you will get on well in the mountains. Clearly a shared language is important, especially if you are to learn from your guide. Most guides speak Berber and French and, increasingly, English, too.

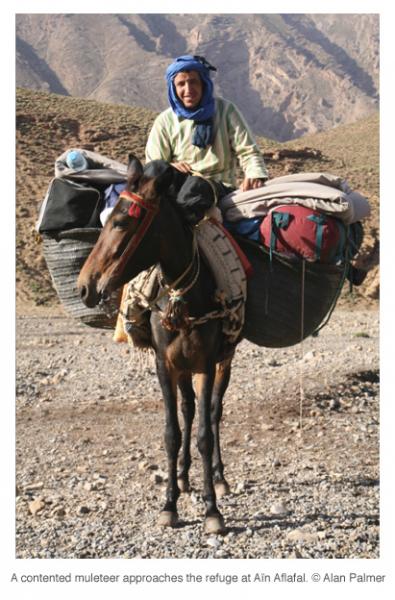

Mules and muleteers

In districts like the Atlas, mules are more serviceable than any horse, and on the mountain roads will perform almost a third longer journey in a day.

R B Cunninghame Graham, Mogreb-el-Acksa, 1898

It is the custom in the Atlas for mules to carry baggage; locals will think it bizarre should you wish to carry your own. You should employ a muleteer as by so doing you not only respect local tradition but also you put money straight into local pockets. This even makes your trek safer since evacuation by mule is often the fastest way out of the Atlas in an emergency (see Mountain rescue, p41). Your guide will almost certainly expect to take responsibility for finding a muleteer for you, who will often be a family member or family friend.

The muleteer will stack what appears to be an enormous amount of baggage onto his mule but, if you fear for its safety, remember that this animal is a very expensive asset to him and he will not risk its health. In fact each mule carries about 100kg which usually equates to only about four rucksacks.

Despite his burden, do not even think about setting your pace against that of your mule. Your muleteer will set his own variable pace, his reasons often only truly understood by himself. In the morning he will usually be last to set off, so as to shut down camp after you have started to walk, but then race ahead of you to set up the next, often taking a different, more mule-friendly route.

For these reasons alone, never make the mistake of employing a muleteer as a cheap form of guide: it is not his job to walk with you and his choice of route will sometimes be restricted to less interesting, lower-level paths with gentler inclines. Indeed, while it is certainly true that most muleteers know their way round the mountains as well as guides, attempting to use a muleteer as a guide would be heavily frowned upon. Equally, never suggest paying a little extra for your guide to carry your pack as he would find such a proposal insulting.

Cuisinier

You will need to plan your food and water carefully before you depart from the trailhead. Whereas on some treks it would be quite possible on most days to eat meals prepared in refuges and gîtes along the way, notably around Toubkal, on other days and on other treks, such as in Jbel Sahro, this would be quite impossible and buying even basic provisions en route in mountain villages to prepare your own meals would be very problematic (see Eating in the Atlas, pp82-3).

It is the custom that you should pay for the food of your guide and muleteer while on the trek. Usually this involves employing your muleteer to double up as a cuisinier (cook), although you could employ a separate cuisinier. The cuisinier, usually with the help of your guide who has a vested interest in overseeing what will be eaten on the trip, will help you budget and buy food for the entire trip (see Budgeting and costs, pp19-21). If you negotiate a price tout compris (everything included), you will not even have to concern yourself with shopping for the food. It might sound rather indulgent to employ a cook but this is the accepted way of doing things.

Gîtes d’étape, refuges and camping

In summer the prospect of sleeping under the stars becomes a very tempting proposition, although on the higher slopes nights can become very cold even on still nights. Moreover, the weather can be very unpredictable and a tent (see What to take pp28-9) is strongly recommended as insurance. In winter, overnight temperatures plummet well below freezing in the High Atlas and, on the trail in the more southerly Sahro and Sirwa areas, nights can become very cold, too, even in spring and autumn (see When to go, pp21-3), so good-quality camping equipment is advised.

Remember to ask permission to camp whenever possible and always tidy up afterwards (see Environmental Impact, pp88-9). You will enjoy greater freedom if you take a tent and at times camping will be the only option open to you.

The Atlas is more populated than might be expected so, if camping is not your preferred option, you will often, but not always, find a village to stay in overnight. A large number provide simple accommodation in a basic gîte d’étape, which typically costs £4/US$6/50dh per night. Alternatively, the nature of Berber hospitality is such that, if you find yourself in a village with no gîte, or if it is full, there’s a good chance you will be offered accommodation by a local family in a private house. Many trekkers prefer to take such opportunities to gain an insight into daily Berber life. Clearly, there is no set rate for such hospitality, but you should not expect to pay more than the price of a gîte.

There are also a few scattered refuges (mountain huts) in the High Atlas, some managed by Club Alpin Français (CAF), which can cost as little as £3/ US$4.50/35dh for a bed in a dormitory . Both gîtes and refuges will often provide drinks, meals and even hot showers for an extra charge; refuges may also offer cooking facilities. Don’t, however, expect five-star luxury. Even the better Atlas accommodation can be quite uncomfortable by European standards. The locations of refuges and gîtes are included in the route descriptions in Part 6.

GROUP TOURS

People join organised treks mainly because it is convenient but there are other advantages: there is a greater chance that your guide will speak your language and you might find yourself in a group of friendly, like-minded people. Certainly, this is one way of avoiding trekking solo. Many agencies combine trekking with other Moroccan ‘highlights’, such as the ‘Kasbah Trail’ or ‘Imperial Cities’, or other mountain activities. If you are looking for a higher level of comfort on your trek, the better agencies are likely to be able to provide this. Also, if you book through a company in your own country, you will probably find a representative on hand in Morocco to ensure that all runs smoothly.

On the downside, group tours are relatively expensive. Expect to pay about £600/US$900 for a one-week trek as part of a group in the Toubkal region excluding flights or about £800/US$1200 including flights. Also on the downside, group tours tend to follow a fixed itinerary. You might find that a group trek proceeds at a different pace to yours, typically adopting a mean speed which can be rather slow. What is more, trekking with a large group of the same nationality can put up barriers between you and the very local culture that you went to Morocco to experience.

If you do decide to take the group option, however, an internet search will quickly throw up a bewildering choice of both international adventure travel companies and Moroccan specialists offering a range of Atlas itineraries. You will also find a host of Moroccan-based trekking agencies and even freelance guides. These local agencies tend to be cheaper than their overseas competitors and, with the advent of the internet and email, are now much easier to make arrangements with than they were even in recent years. Ironically, the overseas-based agencies tend in any case to sub-contract to these Moroccan-based agencies to carry out their work for them, in the process draining potential revenue away from Morocco and into their own pockets. If you want local people to gain most benefit from your visit, employ local people directly.

Latest tweets