Wonderful handbooks

— The Bookseller

The Silk Roads

Excerpt:

Planning your trip

Contents list | Introduction | Planning your trip | The Middle East - practical information for the visitor | The Silk Road route maps | Sample city guide: Samarkand

Routes, costs and making a booking

ROUTE OPTIONS

The fundamental choice, of course, is that of direction. Europeans will probably want to begin in the West and track Marco Polo eastwards. But for others it may be easier to follow John Keats’s poem The Eve of St Agnes: ‘From silken Samarkand to cedar’d Lebanon’ – after all, this was the way the silk came.

It doesn’t, in fact, make much difference and we have tried to accommodate both options in the guide (though it is set out west to east). The real Marco Polo addict might want to emulate William Dalrymple and begin in Jerusalem, though the visa hassles this throws up make it a tricky option (see p17); others might side with Nick Danziger and judge the only true way to complete such a trip is entirely by land from your front door, in which case you can take the train from any European capital through Eastern Europe to Turkey and join this guide in Istanbul. Then again, you might not be able to complete this trip in one go, so we have chosen Istanbul, Tashkent, Islamabad and Beijing as the four most practical (and cheapest) points to start and finish. In Central Asia, however, politics has made Tashkent a less viable option (see p200), so Bishkek and Almaty are increasingly attractive start/finish points. In China, new international routes out of Xi’an are being launched every few months, making it a useful alternative start/finish point, especially if you have visited Beijing on a previous trip.

More significant in your choice of route should be the time you have available. There are numerous shortcuts which we point out and you may choose to miss out some of the excursions but we assume that most of you have chosen this guide because you specifically want to complete the Silk Road from one end to another which means at least 8000km lie between you and your finishing point. We are also assuming that you wish to complete the trip ‘overland’ and have therefore largely ignored internal flight options.

As a rule of thumb we suggest you allow at least six weeks in the Middle East, a month in Central Asia, six weeks to loop through China and two weeks in Pakistan. The Polos, of course, took years and Danziger nearly as long but, if you are in a real hurry, three months gives you just about enough time to see everything on the Silk Road’s main artery between Istanbul and Beijing – although it doesn’t allow for much leeway should anything go wrong.

Because of the political situation, Iraq (see pp78-9) and Afghanistan (see pp10-11) have largely been avoided, despite their clear importance to the Silk Road. Parts of both countries are accessible in one way or another, however, so do not be too put off from visiting. A similar problem faces anyone wishing to traverse the 18,000ft Karakorum Pass linking Khotan and Kashmir: for centuries this was used by Buddhist pilgrims but it has not been open because of a dispute between China and India over the exact border position (plus, of course, there’s the whole Kashmiri problem).

Even without such man-made obstacles it would still be almost impossible to follow some of the old routes: paths have evolved – most obviously the Karakorum Highway which runs up the opposite bank of the river to the old Silk Road path – and some cities on the modern Silk Road lie ten or twenty miles away from their original sites, whether for political or environmental reasons. Others, like Bactria/Balkh (once a ‘Paradise on Earth’) have been erased forever and, along with them, many passes through the mountains have been swallowed up – at the Road’s zenith such passes would have been kept free of snow by regular traffic but now they present the traveller with an immovable white wall.

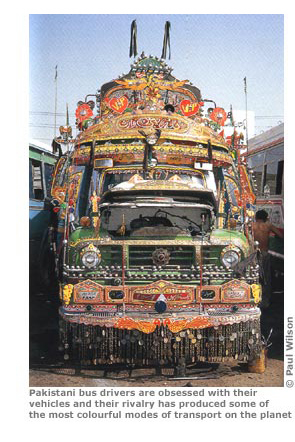

The other difficulty with following the original Silk Road, or at least locating it (and you can find yourself drawn into arguments for hours over this if you’re not careful) is that wherever you go locals will not stop telling you how important their part of the Silk Road is. For the Chinese all Silk Roads begin in Xi’an but whether they went to Central Asia, Afghanistan, India, Korea, Japan or Burma (which they all did at some time) is of little consequence to them because the road was built for their prize export only – nothing important, so they would have you believe, came back the other way. Speak to a Turk and the destination of all the Silk Roads was Constantinople whereas an Egyptian will champion Alexandria. Mongols will stress the importance of their lands and Kublai Khan’s old capitals at Beijing and Xanadu, while Pakistanis will tell you how important their section through the Karakorum Mountains, the Hunza Valley and the Khyber Pass was – much to the annoyance of a Tajik who will swear that from Xinjiang most caravans preferred to cut across the Pamirs through Tajikistan. Finally, to this day, you can meet people who refuse to admit the Silk Road ran through the Caucasus.

Much of the romance of the Silk Road, however, lies in its myth, so don’t be hypercritical, or too pedantic, and enjoy what there is on offer.

COSTS

‘Betwixt Aleppo and the Mogul’s court, victuals being so cheap, that I often-time lived competentlie for a pennie sterling a day.’ Thomas Coryate, 16th-century English traveller.

The cost of your trip can vary wildly and is not helped by the fluctuating value of most of the currencies involved; because of this most major expenditures in this guide are in US dollars – see ‘Money’, p24.

Hidden costs also mount up and the most significant of these (after visas) are entrance fees. We cannot stress enough the advantages of carrying, if at all possible, an International Student Identity Card (ISIC). To get one you are required to prove that you are in full-time education but this process is not always strictly adhered to and something that suggests you’re a student, like a National Union of Students card, which is more easily obtained, might suffice. If you are not eligible for either of these, try to lay your hands on something because in certain Silk Road countries you will receive as much as 90 per cent off the tourist price. Indeed, we estimate a card could save you a few hundred dollars during the trip as it is also valid for some bus journeys and even hotels. If you cannot get some sort of ID, you may still want to ask for the student rate at every opportunity because you are not always asked for proof.

Some of the countries you will visit are still cheap – although the days of backpackers in China never paying more than a dollar for a meal are sadly gone – but you must appreciate that the distances you are going to cover are enormous and this trip cannot be compared, financially at least, to beach-bumming around Thailand.

We have rejected the ‘What can we eat/see/sleep on for less than a dollar?’ approach and if something is worth doing, even if it is relatively expensive, we have recommended it. Having said that, we have avoided the other extreme as exemplified by one of Leo Tolstoy’s descendants who hired her own personal camel, horse, guide and 4WD to complete an expedition from Merv to Xi’an (Ms Tolstoy’s account of the journey, The Last Secrets of the Silk Road, is one to miss).

If money isn’t a problem, you might pay other people to organise this trip for you; and you can stay in five-star hotels at over half the stops along the way. For those hoping for no more than to travel independently, stay in clean accommodation and have the occasional treat, however, we would budget for US$30-US$40 a day depending on whether you have a student card or not and how much you eat, drink and smoke. The longer you go for, of course, the cheaper it gets per day as the travel and entrance costs are more spread out; bottom-line budget travellers can manage on around US$20 a day but they should be prepared to lose weight.

WHEN TO GO

Bear in mind that most of the routes that make up the Silk Road skirt around or plough straight through deserts, so that in mid-summer (June, July and August) the heat is fearsome. In Turkmenistan’s Karakum Desert summer temperatures go up to 45°C in the shade, while in Turfan it is possible to cook an egg merely by placing it in the sand (the highest recorded temperature here is 49.3°C/121°F). The good thing about the heat, though, is that it is a dry heat; while this means that you’ll die faster if you aren’t careful, at least you won’t be feeling sticky and clammy as you go.

At the other extreme, winters in the mountains surrounding China can be deadly cold and two of the main routes – the Torugart Pass and the Karakorum Highway – can be closed by snow from October to March or April (they are officially closed between November and February) while Sir Aurel Stein was hit by a snowstorm in the Pamirs in July!

If you can, you want to avoid the heat as much as possible but this is easier said than done if you are travelling for four months or more. Our advice, especially if you are going west to east, is to begin in April and finish in July. This way the weather is already bright and sunny when you are in the Middle East (although you might see snow in the Turkish mountains), Central Asia and China won’t be too hot and by the middle of summer you are in the relative cool of the Pakistani mountains. This plan beats the autumn alternative, as from September the weather deteriorates and while that’s good for your body it can be disappointing for photos.

The final factor you really ought to consider is that in August the Chinese are on holiday. Most families still cannot afford or are not allowed to holiday abroad so China’s 1.6 billion population tends to visit its home-grown attractions, turning most forms of travel, accommodation and sightseeing into an overcrowded nightmare.

Latest tweets