These Trailblazer guides … are a godsend for independent travelers.

— Travel & Leisure

Tibet Overland

Excerpt:

Introduction

Contents List | Introduction | Planning Your Trip | Mountain-biking in Tibet | Sample route guide

'Tis the Dreamer whose dreams come true!' Rudyard Kipling

Hundreds of books written in contemporary times wax lyrical about the lure of Tibet. Nonetheless, no matter how many people visit Tibet, it remains an extraordinary destination.

The purpose of this book is to help travellers to explore Tibet in a new way and, where possible, avoid the commercial trappings of ‘bottled tourism’ that have become commonplace in the region. With this guide, a bit of independence and a decent measure of determination and good humour, you can have a unique overland adventure on the Roof of the World.

Tibet – a destination and a journey

The magic and mystery of Tibet have lured travellers for years. Until the turn of the 20th century, Tibet was one of the few destinations in the world that was so unattainable that it would tantalize adventure travellers from all corners of the globe. Its geographic isolation on the highest plateau in the world and unique culture and religious beliefs have for centuries moulded the lives of a very special people. For years, hearsay and Pundit rumour were all that the outside world could learn about this secret land and its inhabitants.

The Tibetan civilization is one of the oldest in the world, dating back 5000 years at least. It is almost certainly much older than this. The mythical history, according to Bon tradition, describes the Tibetan people as descendants of a Simian father and a mountain ogress. The offspring inherited their father's compassion and their mother's stubborn character. When travellers meet the Tibetan people living on the plateau today, they may wonder if there is some truth to their mythical ancestry.

Of equal importance is the environment that has shaped the Tibetan people. Tibet is bordered to the south by the Himalayas and to the west by the Ladakh mountains and the Karakoram ranges. To the north are the Kun-Lun and Tang-La ranges. The sole gap between the magnificent mountains that isolate the plateau is to the east where three mighty rivers flow. These are the three main rivers in Asia that find their source in Tibet: the Indus, the Brahmaputra and the Yangtse.

Tibetans call their home ‘Land of the Snows’. It is often referred to as the ‘Roof of the World’. Both names capture the extreme nature of the land. Covering an area of about 2.5 million sq km, the average altitude on the plateau is more than 4000m. The extreme climate renders 75% of the land uninhabitable, making Tibet one of the world's least populated regions.

Since 1951, just as the Western world was beginning to catch its first real glimpse of life in Tibet, the Chinese government closed its doors. These remained closed until the early eighties. China's so-called ‘peaceful liberation’ of Tibet in 1959, promoted under the policy of ‘Reunification of the Motherland’, has impacted significantly on both the land and its inhabitants. The ancient civilization now coexists with Communist China.

Yet despite the difficulties created by the presence of the Chinese authorities, travel to Tibet is still completely worthwhile. China has recognized the economic value of tourism in Tibet and identified it as one of ‘five pillars of industry’ necessary for the economic development of the region. As a tourist you are able to take advantage of this approach and travel relatively freely in all open areas.

Although the policies introduced in the country since 1959 have transformed Tibet's cities, the land and the people outside the city centres continue to retain many aspects of traditional Tibet. The thin mountain air creates an almost surreal effect on the landscape. The mountains and lakes have an overwhelming presence and remain enduringly holy and sacred to the people. These things have not changed since 1959. In many ways, the Tibetan way of life, particularly outside the major cities, continues in the same manner as it has done for thousands of years. Unfortunately, Chinese policies are extending into remote rural areas, and it is possible that these ancient traditions may become a thing of the past – and that would be a tragedy.

If you have any doubt that your presence as a tourist in Tibet may contribute to the decline of the traditional Tibetan way of life and condone the Chinese presence and control over Tibet, consider the advice of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, who is recognized by most Tibetans as the spiritual and temporal leader of Tibet. The Dalai Lama maintains that informed and aware tourists have an important role to play in the preservation of Tibetan culture and he has a clear message for travellers to his homeland, as stated in the Foreword to this guidebook:

. . . I encourage anyone who wishes to go to do so.

Overland travel in Tibet

Tibet is the ultimate overlander's paradise in terms of the scope for excitement and adventure. Adventure travellers and visitors to Tibet are often of the same mindset. Any individual who seeks an exciting travel experience that permits a real insight into a culture should consider an overland journey to Tibet – the cream of ‘off the beaten track’ travel.

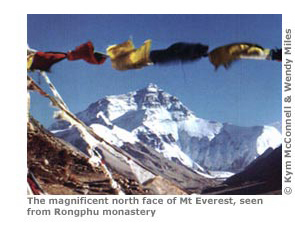

Mountain biking in Tibet is the ultimate off the beaten track adventure. There is nowhere else in the world where mountain bikers are able to cycle alongside 8000m-plus peaks and conquer 5000m-plus mountain passes – almost daily. it's even possible to bike to the foot of the highest mountain on earth. Tibet boasts the world's longest downhill run – from a high point of just under 5000m at Lalung la to below 800m in Nepal, in just over 160kms of incredibly exhilarating descent. To add to that, road quality and extreme weather conditions make mountain biking in Tibet technically challenging – particularly off the main routes.

Mountain biking on the highest roads in the world is a physically and mentally demanding challenge but the rewards are extraordinary. The personal satisfaction and thrill achieved from such a trip can be enormous. Difficult and often exhausting conditions combine to test your fortitude. But the view of the world from the dizzying heights of Tibet and the long, lonely expanse of solitude that envelops you is a humbling experience. Inevitably, your view of the world, and of yourself, will never be the same again.

Regardless of your chosen mode of transport, Tibet is a perfect setting for an adventure. The secret, jealously guarded by the few travellers who have already travelled overland in the region, is that this mode of travel makes it possible for travellers to live with the Tibetan people and discover the traditional Tibetan way of life outside the big modernized cities. For example, on most overland routes recorded in this book it is not possible to reach the next major township within one day of cycling. Accordingly, mountain bikers will be required to camp with nomads or negotiate accommodation at local villages or monasteries. In doing so you will catch an insight into nomadic, village and monastic life that is very difficult to achieve unless you have completely independent transport.

In an overland travellers’ (particularly cyclists�) daily search for food outside the main towns, the renowned hospitality of the Tibetan people is inescapable. Bikers are frequently invited off the road to share a cup of butter tea and a bowl of tsampa. It would be misleading to suggest that all of these aspects of overland travel in Tibet are entirely pleasant. In particular, some of the most magical, and at times most frustrating, characters encountered by mountain bikers are the local children. Tibetan and Chinese children literally mob cyclists passing schools and villages. The playfulness of the children on the plateau will drive you to distraction. But look at it from their point of view: mountain bikers are an exciting and refreshing sight in their isolated environment and a welcome distraction from schoolwork and the never-ending task of collecting yak dung for the fire. If you spend the time winning the favour of the village children, you will inevitably find that their parents are much more willing to accommodate your needs!

How to use this guidebook

The aim of this book is to provide overland travellers in Tibet with the most accurate maps and route descriptions. The overland routes on pp63-146 were researched by me and are accompanied by maps, elevation profiles and km-by-km route descriptions. The routes on pp147-71 were compiled from a mixture of my own research and other friends’ and travellers’ notes.

Maps The maps included in this book have been painstakingly created by Claude André from a voluntary group in France called the Tibet Map Institute. M. André has been involved with cartography on the Tibetan plateau since 1967; the Royal Geographical Society published some of his early research. The impetus for his recent work is the lack of credible maps produced since the 1950s identifying and locating the Tibetan villages and monasteries destroyed by the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution.

The Tibet Map Institute (website: www.tibetmap.com) has now produced over 80 maps (scale 1:310,000) together with a database of over 7000 toponyms. The maps are based on NASA Landsat photographs superimposed onto international aeronautical maps and they incorporate the most accurate altitudes/features available from various sources (including everything from the earliest explorers’ and Pundits’ notes to the most recent traveller data).

At my request for assistance, M. André kindly adapted some of his maps to illustrate the key overland routes detailed in this book including distance and altitude readings. Scales for the maps are as follows: Maps 1 and 3 (1:450,000), Maps 2, 4-8 and 10 (1:500,000), Map 9 (1:300,000). During my research I found various road maps (see p32) but none had the accurate distance readings or elevation profiles required by cyclists. Whilst a 20km error is generally irrelevant for motorists it can mean two or three hours of extra cycling at the end of an already hard day for mountain bikers!

Elevation profiles The elevation profiles in this book are generated from the altitudes recorded religiously along the way and should assist you in anticipating the severity of your daily route.

Relative or absolute It is the relative, not absolute, heights that are important when travelling in Tibet. The accuracy of any map series is only relative to the ‘base’ or reference coordinates upon which it is created. Because the Chinese have not allowed anyone to officially ‘map’ Tibet for 50 years, the altitude readings provided by the different recognized topographical map series vary (see ‘Maps – topographical’ pp31-2). For example, the height of Mt Nyenchen Thangla (north of Lhasa) is recorded at the varying heights of: 7090m (Russian World Series); 6986m (US Tactical Pilot Chart Series); 7111m (US Joint Operations Graphic Series); and 7117m (Chinese Series).

Also, the recorded altitudes for Lhasa city vary between 3600m and 3680m. For the sake of simplicity all altitudes in my route descriptions are based on an altitude for Lhasa (Barkhor Square) of 3600m.

Another example of inconsistencies is the stone marker readings on top of most passes in Tibet, which never seem to agree with (or differ by the same amount from) any traveller's altimeter.

Route guides

The route guides in this book provide a km-by-km breakdown of popular overland routes including points of interest, villages, mountain passes, possible campsites, and the main places to buy food, water or seek accommodation. They are not exhaustive as there are many additional compounds or groups of houses where you could also barter for sustenance or shelter. Firstly, tours are described that travellers will be able to complete in less than one week (to Ganden, Nam Tso or the Yarlung Valley) using Lhasa as a base. Secondly, there is a detailed description of the ‘classic’ overland route in Tibet from Lhasa to Kathmandu including the side trip to Mt Everest North Base Camp.

The final route guides in Part 3 cover the long overland journeys into Lhasa from Xining, Kunming and Kashgar and provide an overview and indication of the distances and main passes between key villages along the way. Note that these routes do not always contain information such as road markers, and some altitudes may not be exact where they have been collated from secondary sources.

Distances All the distance ‘cyclometer’ readings originating out of Lhasa commence from Barkhor Square. It is anticipated the daily distance measurements could vary up to 1km per day between different individual cyclists, depending upon how straight cyclists ride, especially on uphill sections of the passes.

Road markers In Tibet there are very few road signs but most of the main overland routes have stone markers on the shoulders of the road, supposedly at 1km intervals. The distance readings on various markers can be a little confusing as they can commence from different origins (some start from Beijing!). Also, as the roads are redeveloped the stone markers get updated or replaced and a new system may be totally unrelated to the old one. At least four different marker systems (in black or red) are in use just between Lhasa and Kathmandu.

The kilometre marker readings are recorded in the route guides throughout this book. Sometimes an approximate reading is given where the marker is missing. Where a particular ‘point of interest’ lies between two markers, both markers are recorded (eg 165/166 as seen in the above extract). Remember that the cyclometer on your bike or the odometer reading in your vehicle may not always equate with these markers.

Cycling times Approximate cycling times (excluding rest breaks) are also given to allow you to plan the maximum or minimum time it will take you to get between points (weather dependent, of course!). I had full rear panniers throughout Tibet but cyclists on organized tours (where all gear is usually carried by a supporting vehicle) can expect shorter times.

Special issues for travellers in Tibet

It is important for travellers to the region to understand something about the political situation in Tibet. The political climate is turbulent and rules and regulations governing individual travellers are liable to change with little or no notice. If you understand something about the historical facts that led to the current situation, you will better appreciate the reason why certain things are as they are. Whether you intend to or not, your very presence there will have an impact both on the lives of the Tibetan people and of the Chinese living in Tibet.

Most people contemplating travel into the region will have heard of the Dalai Lama, the Tibetan religious leader who fled from his homeland in 1959 when the Chinese army took control of the capital city of Lhasa. See p181-91 for an introduction to Tibetan history (which I have tried to relate in an objective manner). The unfortunate reality is that the events since the Dalai Lama fled to neighbouring India cannot be dismissed purely as a matter of historic interest only. Those events, and the continued presence of the Chinese people in Tibet today, have an immediate effect on the lives of both the people living on the plateau and the tens of thousands of Tibetan refugees currently living in exile. Each year thousands of new Tibetan refugees arrive in Dharamsala, Northern India, the home of the Dalai Lama and his Government-in-Exile. Many more enter other Tibetan refugee camps in India, Nepal and Bhutan.

Chinese policies continue to undermine Tibetan culture. Things that are fundamentally Tibetan, such as Tibetan Buddhism, the nomadic way of life, monastic living, the Tibetan language and food, all comprise a living and breathing culture that is quite different from the culture and traditions of the Chinese. This poses a threat to China as it strives to redefine Tibetans as a ‘minority ethnic group within China’ to be preserved by a ‘Cultural Ministry’ for display on appropriate state occasions and to tour parties. Whilst some of the major monasteries are undergoing reconstruction, largely funded by the Chinese administration, ancient scriptures also are being redrafted so as to exclude the doctrines that the Chinese find offensive or ‘separatist’. The new open religious practice is in fact very severely constrained.

For example, in 1996 a campaign of ‘patriotic re-education’ commenced in all major monasteries in Tibet. Monks were forced to denounce the Dalai Lama and destroy all photographs of His Holiness. Since 1996 more than 12,000 monks and nuns have left or been forced out of monasteries and nunneries because they were unwilling to comply with China's demands. Religion is only one aspect of repression in the ‘new open Tibet’. There were reported shootings by the Chinese authorities in Lhasa in April 1998, leading to the deaths of seven monks. In 2001 there were at least six reported executions in Tibet as a result of a renewed wave of the so-called ‘Strike Hard’ campaign which aims to crack down on crime.

Travellers to the region need to be aware of the political issues – it is possible that you could become involved (directly or indirectly) with such issues. Travellers on bicycles must be particularly cautious as they will often avoid the controls that have been established by the authorities to shield the Tibetan people from foreign visitors (and vice versa).

Awareness of the issues and a sensitive and sensible approach to your environment and the people in it will enhance your Tibetan experience. It will help you to understand why people behave in a certain way and how they react to you – a foreign visitor. Try to be aware that conversations in major centres, such as Lhasa, may be monitored. The Potala Palace in particular is equipped with an extensive video and infra-red sound surveillance system. In addition, there is a far-reaching network of ‘informers’ operating in major tourist spots and monasteries. Conversations of a ‘political’ nature will be most likely to draw the attention of the authorities. There are accounts of nuns and monks reporting travellers to the authorities on the grounds that they illegally engaged in political conversations or distributed banned material (such as photographs of the Dalai Lama or Tibetan flags). In 1995 a guest at the largest tourist hotel in Lhasa was detained for 48hr by police for speculating about a bomb explosion in a facsimile that he had sent home. In October 2001, three foreign tourists were detained in Lhasa after displaying a Tibetan flag and shouting pro-independence slogans in front of the Potala.

In reality, the worst thing that is likely to happen to a tourist who is suspected of ‘unlawful’ activity is that he or she will be interrogated and deported. Any Tibetan who is caught receiving or distributing incriminating material is liable to a lengthy term of imprisonment and, possibly, torture at the hands of the Chinese authorities.

Admittedly, the growing number of tourists in Lhasa makes it increasingly difficult for the Chinese authorities to monitor everybody. The key is to keep a low profile in the major city centres. If you do not draw attention to yourself then you and your mountain bike will be permitted to move about virtually unhindered by the authorities (also see the visas and permits section, pp20-2).

Latest tweets