'These human-scale books, written and published by people who genuinely know and love their subject, are perfect for travel's post-pandemic recovery.'

— The Guardian, March 2021

Trans-Siberian Handbook

Excerpt:

Sample Route Guide: Trans-Siberian Route and map 1

Contents | Introduction | Individual itineraries or organised tours? | Route planning | What to take | Sample Route Guide: Trans-Siberian Route and map 1 | Other railway lines linked to the Trans-Siberian | Best of Trans-Siberian

USING THE GUIDE

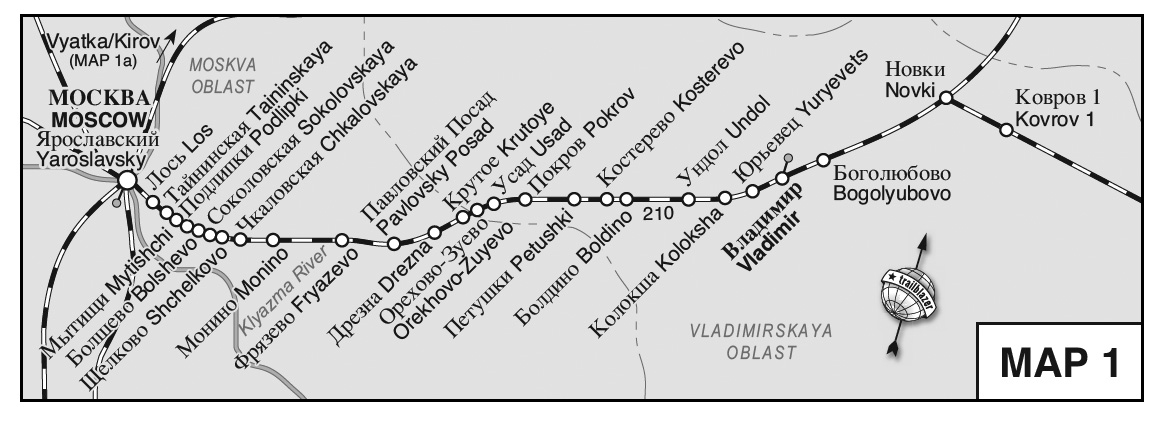

This route guide has been set out to draw your attention to points of interest and to enable you to locate your position along the Trans-Siberian line. On the maps, stations are indicated in Russian and English and their distance from Moscow is given in the text.

Stations and points of interest are identified in the text by a kilometre number. In some cases these numbers are approximate so start looking out for the point of interest a few kilometres before its stated position.

Where something of interest is on only one side of the track, it is identified after its kilometre number by the approximate compass direction for those going away from Moscow; that is, on the Moscow–Vladivostok Trans-Siberian line by the letter N (north or left-hand side of the train) or S (south or right-hand side), and on the Trans-Mongolian branch and Trans-Manchurian branch by E (east or left-hand side) or W (west or right-hand side).

The elevation of major towns and cities is given in metres and feet beside the station name. Time zones are indicated throughout the text (MT = Moscow Time). See inside back cover for key map and time zones.

Kilometre posts

These are located on the southern or western side of the track, sometimes so close to the train that they’re difficult to see. The technique is to press your face close to the glass and look along the train until a post flashes by.

On each post, the number on the face furthest from Moscow is larger by 1km than that on the face nearest to Moscow, suggesting that each number really refers to the entire 1km of railway towards which it ‘looks’.

Railway timetables show your approximate true distance from Moscow, but unfortunately the distances painted on the kilometre (km) posts generally do not: indeed on the Trans-Siberian they may vary by up to 40km, the result of multiple route changes over the years. Distances noted in the following route guide and in the timetables at the back of the book correspond to those on the kilometre posts.

Occasionally, however, railway authorities may recalibrate and repaint these posts, thereby confusing us all! If you notice any discrepancies, please write to the author (see p4).

Station name boards

Station signs are sometimes as difficult to catch sight of as kilometre posts since they are usually placed only on the station building (over the last couple of years, RZD have replaced most station signs with bright new ones in Russian and English) and not always along the platform as in most other countries. Rail traffic on the line is heavy and even if your carriage does pull up opposite the station building you may have your view of it obscured by another train.

Stops

Where the train stops at a station the duration of the stop is indicated by:

l (1-6 mins) ll (7-14 mins) lll (15-24 mins) lll + (25 mins and over)

These durations are based upon timetables for the 001/002 Moscow–Vladivostok (Rossiya), 003/004 Moscow–Beijing (Trans-Mongolian) and 019/020 Moscow–Beijing (Vostok, Trans-Manchurian) services. Actual durations may vary widely as timetables are revised, and may be reduced if a train is running late.

Route timetables that hang somewhere near the provodnitsa’s office tell you exactly how long each train stop should be. Provodnitsas do not let you get off if the stop duration is less than five minutes. At longer stops, don’t stray far from the train as it will move off without a whistle or other signal (except in China) and passengers can be left behind. If the train is running late, longer stops can be cut short.

Time zones

All trains in Russia run on Moscow Time (MT). Siberian time zones are listed throughout the route guide; major cities include Novosibirsk (MT+3), Irkutsk (MT+5), Khabarovsk (MT+7) and Vladivostok (MT+7).

Moscow Time is four hours ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT+4) year-round, as Russia currently does not observe Daylight Savings Time. Note that China has a single time zone, GMT+8, for the whole country and for the whole year. Mongolian Time is GMT+8 year-round, as Mongolia also does not observe daylight saving time.

TRANS-SIBERIAN ROUTE (Sample)

Km0: Moscow

Yaroslavsky Station Most Trans-Siberian trains depart from Moscow’s Yaroslavsky station (see p203), on Komsomolskaya pl (M Komsomolskaya). Yaroslavsky station is very distinctive, built in 1902 as a stylised reproduction of an old Russian terem (fort), its walls decorated with coloured tiles.

Km13: Los Just after this station, the train crosses over the Moscow Ring Road. This road marks the city’s metropolitan border.

Km15: Taininskaya A post-Soviet monument here, dedicated to Russia’s last tsar, Nicholas II, says, ‘To Tsar Nikolai II from the Russian people with repentance’.

Km18: Mytishchi is known for three particular factories. The railway carriage factory, Metrovagonmash, manufactured all the Soviet Union’s metro cars and now builds the N5 carriages to be seen on Moscow’s metro. Mytishchinsky monument factory, the source of many of those ponderous Lenin statues that once littered the country, has at last been forced to develop a new line. It now churns out the kind of ‘art’ banned in the Soviet era: religious statues, memorials to the victims of Stalin’s purges and busts of mafia bosses. Some of its earlier achievements displayed in Moscow include the giant Lenin in front of Oktyabrskaya metro station, an equestrian statue of Moscow’s founder, Yuri Dolgoruky, on Tverskaya Ploshchad, and the Karl Marx across from the Bolshoi Theatre.

Production has also slowed at the armoured vehicle factory, one of Russia’s three major tank works, the others being in the Siberian cities of Kurgan and Omsk.

The smoking factories and suburban blocks of flats are now left behind and you roll through forests of pine, birch and oak. Amongst the trees there are picturesque wooden dachas (see box opposite) where many of Moscow’s residents spend their weekends. You pass through little stations with long, white-washed picket fences.

Km38: Chkalovskaya On your right-hand side (S) you’ll see an aeroplane monument with the Russian inscription: ‘Glory to the Soviet conquerors of the sky,’ commemorating Chkalov, a famous pilot and Soviet hero (see p241) who was the first man to fly nonstop from Moscow via the North Pole to Vancouver (Washington, USA, not Canada) in 1937.

Km41: Tsiolkovskaya Close to the station lies Zvyozdny Gorodok (Star City), the space research centre where Russian astronauts live with their families and where they have trained for various space missions from the 1960s onwards. This part of Russia was off-limits to foreigners until 1989.

Km54: Fryazevo This is the junction with the line to Moscow’s Kursky station. Although km posts here say 54km you’re actually 73km from Moscow’s Yaroslavsky station (see box p429).

(Turn to p505 if you’re travelling via Yaroslavl).

Km68: Pavlovsky Posad This ancient town is a centre of textile manufacturing.

Km90: Orekhovo-Zuyevo The town, at the junction with the line to Aleksandrov, is also the centre of an important textile region. It gained its pre-revolutionary credentials in 1885 with the Morozov strike, the largest workers’ demonstration in Russia up to that time.

Km110: Pokrov It was in the nearby village of Novoselovo that Yuri Gagarin, the world’s first astronaut, died in a plane crash in 1968. He was piloting a small aircraft when another plane flew too close. The resulting turbulence forced his aircraft into a downward spin which he was unable to correct.

Km126: Petushki If you ever see a Communist-era film with bears in it, chances are it was shot in the countryside around Petushki. The town’s best-known attraction is the nearby zoo, source of many animals used in Russian movies. Petushki sits on the left bank of the Klyazma River.

Km135: Kosterevo The 19th-century painter Isaak Levitan lived near here. His house has been moved into Kosterevo and opened as a museum.

Km161: Undol The station is named after Russian bibliographer V M Undolsky, who was born near here. The town is known as Lakinsk after M I Lakin, a revolutionary killed here in 1905. But the area is probably best known for its brewery, a Soviet-era Czechoslovak joint venture. Lakinsk beer, very popular in the 1990s, is now under strong competition from Western brands.

Km191: Vladimir (lll) [see pp224-9]

Vladimir (pop: 347,930) was founded in 1108. In 1157 it became capital of the principality of Vladimir-Suzdal and therefore politically the most important city in Russia. It’s worth visiting for its great Assumption Cathedral, its domes rising above the city as you approach, and as a stepping-stone to the more interesting town of Suzdal (see pp230-7), 35km away, and the wonderful Church of the Intercession on the Nerl (see below), 10km from Vladimir.

Km202: Bogolyubovo [see pp229-30]

Visible from the train (N) about 1.5km east of Bogolyubovo is the Church of the Intercession on the Nerl, one of Russia’s loveliest and most famous churches. Built in 1165, the single-domed church sits in the middle of a field at the junction of the Nerl and Klyazma rivers. It was constructed in a single summer on the orders of Andrei Bogolyubsky, in memory of his son who died in battle against the Volga Bulgars. It was built on this prominent spot to impress visiting ambassadors. To symbolise Vladimir’s inheritance of religious authority from Byzantium and Kiev the church was consecrated and a holiday declared without permission being sought.

Km240: Novki This large town at the junction of the line to Ivanovo boasts one of Russia’s ugliest stations. The original building is about a century old. In the 1980s, in an attempt to make it appear contemporary, it was encased in pink and fawn tiles. The result is a monumental eyesore.

About 13km eastward the train crosses the wide Klyazma River. The original bridge, built in the 1890s, was washed away in a flood. To avoid the problems of extending a new bridge across the river, engineers came up with a clever alternative. They built a bridge on dry land, on the inside of a bend in the river 1km to the west, then dug a canal beneath the bridge, detoured the river through it and filled in the old river bed. As you pass by you can see the old river course on each side of the bridge’s eastern embankment.

Km255: Kovrov I I This ancient town gets its name from kovyor, the Russian word for ‘carpet’. During the Mongol Tatar’s reign in the 14th century, the local tax collector accepted carpets as one of the tributes. The town’s best-known son was engineer Vasili Alekseyevich Degtyarev (1879-1949), father of the Soviet machine-gun. The Degtyarev factory, founded here in 1916, now manufactures motorcycles, scooter engines and small arms. In the town centre there is a monument to Degtyarev, holding an engineering micrometer rather than a gun. His grave is nearby and his house, at ul Degtyareva 4, has been turned into a museum. Kovrov is also famous for its excavator factory founded in the mid-19th century to build and maintain railway rolling stock. Its claims to fame include the world’s first steam-heated passenger carriage (1866) and Russia’s first hospital carriage (1877). The factory’s importance is illustrated by large, colourful murals of digging machinery on the sides of Kovrov’s nine-storey accommodation blocks.

Km295: Mstera The village of the same name, 14km from the station, is known for its folk handicrafts and has lent its name to particular styles of miniature painting and embroidery. Mstera miniatures, notable for their deep black background and warm, soft colours, usually depict scenes from folklore, history, literature and everyday life. They are painted in tempera (from pigments ground in water and mixed with egg yolk) onto papier-mâché boxes and lacquered to a high sheen. Mstera embroidery is characterised by two types of stitch, called white satin stitch and Vladimir stitch.

Km315: Vyazniki The name means ‘little elms’, after the trees on the banks of the Klyazma River among which this ancient village’s first huts were sited. The town got on the map when pilgrims started flocking here after 1622 to see the miracle-working Kazan Mother of God icon. Vyazniki became famous for its icon painters, with two local masters invited in the mid 17th century to paint cathedral icons in Moscow’s Kremlin.

(The above is an extract from the guide.)

Trans-Siberian Handbook

Excerpts:

- Contents

- Introduction

- Individual itineraries or organised tours?

- Route planning

- What to take

- Sample Route Guide: Trans-Siberian Route and map 1

- Other railway lines linked to the Trans-Siberian

- Best of Trans-Siberian

Price: £16.99 buy online now…

Latest tweets