Guides that will send you packing.

— Today

Trekking in the Annapurna Region

Excerpt:

Minimum impact trekking

Contents List | Introduction | With a group or independently? | When to go | Minimum impact trekking | Sample route

MINIMUM IMPACT TREKKING

Pros and cons of Nepal's trekking industry

Tourism is a vital source of foreign exchange for Nepal. Directly or indirectly many Nepalis benefit from the increasing numbers of trekkers and tourists visiting the country even though most of the money they spend goes to just a few people: the trekking companies, the lodge owners and, of course, His Majesty's Government. How much of the money actually contributes to local village economies is debatable and one study places the figure as low as £0.14/US $0.20 out of the average £2/US$3 spent by a trekker each day. In a country where the annual average wage is just over £100 or US$160 and in a region that sees over 50,000 trekkers per year, however, this is not as inconsiderable as the statistic might suggest. Villages that are situated along the main trekking routes are generally more affluent than those that few trekkers pass through.

Much has been written about the negative effects of trekking. It is very true that trekkers place a far greater strain on local resources, firewood particularly, than do locals. According to ACAP, in one village on a main trail in the Annapurna region, up to one hectare (about 21 acres) of forest is cleared each year for use as firewood for the needs of trekkers.

Forest clearance leads to soil erosion, already a major problem in the unstable Himalayan region. Trekkers make a significant contribution to the pollution problem with streamers of pink lavatory paper and plastic mineral water bottles. Far less obvious are the negative aspects of the cultural impact made by trekkers on local communities.

In the tourist boom of the 1970s and 80s it was realized that the pressures of visitors in popular areas like the Annapurna region could eventually destroy the very environment that attracted the visitors in the first place. Several organizations, the Annapurna Conservation Area Project in particular, have done sterling work in conservation education. Their advice is well publicized but, sadly, not always followed; some trekkers behave as if having paid their trekking fees and lodge bills this gives them the right to behave exactly as they choose. The oft-repeated ‘Nepal is here to change you, not for you to change it’ may sound trite but it is all too true: responsible trekkers should follow this maxim.

The main areas of concern are environmental, economic and cultural. The simple steps that can easily be taken by trekkers to lessen their impact on the delicate ecological balance in the Annapurna region are detailed below.

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

Forest clearance

About 95% of Nepal's energy comes from firewood and the country's forests are being cleared at a rate of 3% per year. Reforestation projects cannot keep pace with this deforestation and the subsequent erosion that often occurs may make the land unusable. A rapidly expanding population and a reliance on firewood for fuel are the main causes of the problem but in a few localized areas, the Annapurna region in particular, trekkers may be more to blame than local people.

it's been estimated that a trekker requires up to ten times the amount of firewood that a Nepali would need. Complicated meals are requested at odd times, hot showers are required immediately and boiled water may be demanded for drinking. In winter, trekkers may want a warm fire to sit around at night.

In a country that has tremendous hydroelectric potential, electricity would seem to be the answer to the problem. At present, most of the power generated in this way is either consumed in the Kathmandu Valley or sold to India. There are a number of micro-hydro schemes in the hills but other than powering a few low-wattage cookers they're used mainly for lighting. it's been said that these lighting schemes may actually lead to a greater consumption of firewood since people are now able to stay up after dark so they keep fires burning for warmth.

In order to lessen your impact on the environment you should:

Have hot showers only at lodges with solar panels or backboilers Some lodges now have backboilers installed in the cooking stove so that extra wood is not used to heat water. Other lodges have solar panels for water heating that can be remarkably efficient (as long as you're not at the end of the queue for a shower). Patronize places like this if you want a hot shower and have a wash in a bucket of cold water in smaller places.

Order meals together and keep orders simple Some of the complicated Western dishes that are requested by trekkers are far from fuel efficient, especially when they are ordered singly. Place your order for supper as soon as you arrive at a lodge so that the lodge owner can bulk dishes together. If you want something for pudding order this at the same time, even though you may prefer to wait until you've had your main course. Order simple things for lunch. Noodle soup is a good choice not only because it's fuel efficient but because it's very quick to prepare. The Nepali staple of daal bhat is cooked in large quantities morning and evening, even in lodges largely patronized by Westerners. it's delicious, filling, cheap and arguably the most environmentally right-on dish you could choose.

don't request boiled water for drinking There are several perfectly good ways of purifying water (see p254) which render boiling unnecessary, as well as the Safe Drinking Water Scheme (see box opposite). If you treat water yourself you can also be absolutely sure that it has been purified, not simply warmed in a kettle. Micropur iodine tablets are available from the all the ACAP offices around the trek.

Put on extra clothes, not another log on the fire Sitting round a fire toasting marshmallows on sticks may be all right in the West but in Nepal it's ecologically more sound to turn in early or put on extra clothes if you're cold.

Use kerosene if you're camping Whilst most trekking companies now use kerosene for cooking for trekkers they do not provide such environmental luxuries for their porters who are forced to cook on fires. it's up to trekkers to lobby trek leaders and the trekking companies if this situation is to change. It has been calculated that to provide kerosene for everyone on the trek would increase the daily cost of a trekking holiday by only £1.50/US$2.25. Kerosene is available in larger villages. There is a total ban on fires in the Annapurna Sanctuary and there's a kerosene depot in Chomrong on the route in. ACAP is setting up kerosene depots around the Annapurna Circuit.

Erosion

it's not only forest clearance that's to blame for the high incidence of erosion in the Himalaya. The world's youngest chain of mountains is still being formed, rising several millimetres per year as the Asian continental plate pushes up against the Tibetan Plateau. Monsoonal rain on the southern slopes causes further erosion as swollen rivers rush down to the lowlands.

This natural erosion makes the erosion caused by forest clearance all the more serious. Approximately 400,000 hectares of forest are cleared in Nepal each year, resulting in the loss of an additional twenty million tons of soil each year.

Stay on the main trail Avoid steep shortcuts since their continued use may erode the hillside. don't damage crops or the edges of rice fields: these surrounding ledges are designed to keep in the water when the fields are flooded.

don't damage plants The age of the Victorian plant-hunter is past and you're unlikely to get your rare rhododendron specimen through customs in Heathrow or JFK, so don't try.

Pollution

Litter is a modern problem. Before the 1960s there was virtually nothing available in the mountain villages that was non-biodegradable, apart from glass bottles. The few items that might be sold in the village shop were wrapped in paper or cloth not plastic. In the lowlands, take-away snacks and meals were and still are served on sal leaves, sewn together and pressed into the shape of a bowl.

In many villages, particularly those on the trekking routes, litter is now a significant problem. Trekkers are certainly to blame for the lavatory paper that may occasionally be seen along the trail and for the piles of plastic mineral water bottles since local people would not use either. A growing cash-based economy has led to greater local use of shops and some Nepalis are still unaware of the cumulative effect of discarding biscuit wrappers, cans or plastic fertilizer bags.

Faecal contamination of water supplies by humans and animals is, however, not a new problem although in many areas drinking water is now piped into the village from a relatively clean source. You should, nevertheless, purify all water for drinking.

don't leave litter Never drop litter on the trail but take it on with you and dispose of it at the next lodge. Even better is to bring a strong plastic bag for all your litter and dispose of it at the end of your trek in Pokhara. Picking up other people's litter would be helpful and set a good example to Nepalis and other trekkers.

If you're on an organized trek burnables should be thrown on the fire and, ideally, non-burnables should be carried out and disposed of outside the trekking area. More usually, non-burnables are buried in a pit dug at the campsite. Stress that this must be efficiently done; although this may be difficult since you will probably leave the site before the kitchen staff.

Avoid bottled mineral water Soft drink bottles and some beer bottles are returnable and therefore environmentally friendly. Mineral water is, however, sold in plastic bottles that are not only non-returnable but also non-biodegradable. Since, furthermore, you cannot be sure that the bottle hasn't been refilled from a tap (the seals are not 100% tamper-proof) it's far better to get water from lodges and purify it yourself or buy water from outlets of the Safe Drinking Water Scheme (see box p88) which is cheaper than bottled mineral water and probably safer.

Dispose of used batteries outside Nepal In her useful booklet, Trekking Gently in the Himalaya, Wendy Brewer Lama has calculated that if every one of the 70,000 trekkers who come to Nepal each year disposes of four flashlight batteries during their stay more than a quarter of a million batteries would be left behind annually. Since the country does not have the facilities for their proper disposal many of these batteries land up polluting the environment or even as children's playthings. Small batteries for cameras could be even more dangerous as toys. Take all used batteries out of Nepal and dispose of them in the West.

don't pollute water sources If there's a latrine available, use it, otherwise ensure you're at least 20m from a water source and bury your faeces. If you're on an organized trek, a hole is dug and a latrine tent erected over it. Sprinkle some earth into the hole after each use and ensure that it is properly filled when you break camp.

don't pollute hot springs with soap and shampoo, whatever local people are doing. Borrow a bowl or bucket from a lodge (or you could even use your mug) and wash away from the spring. Collapsible plastic buckets are available from camping shops in the West. These are particularly useful for clothes’ washing by streams. Dispose of dirty water away from the stream.

Burn used lavatory paper Few Westerners can adapt to the Nepali water-and-left-hand method. They should, however, ensure that the yards of pink Chinese loo paper that they require as an alternative are entirely incinerated or put in the bins provided for the purpose. Keep your roll of paper in a plastic bag with a lighter. don't drop paper down a latrine as this may clog it.

ECONOMIC IMPACT

The economic importance of tourism for Nepal is undeniable. Until recently the people of Lo Manthang and Upper Mustang (closed to foreigners until 1992) must have looked with envy at their rich neighbours to the south in busy tourist villages like Marpha and Jomsom. Given the choice most Nepali village committees would opt to climb aboard the trekking bandwagon. The distribution of these tourist dollars is far from equal, though. Book an organized trek through a foreign operator and a proportion of what you pay stays in the West to pay the company's administrative costs. Book an organized trek in Kathmandu and a large proportion remains in the city. The trek personnel may not be from the Annapurna region and since virtually everything on an organized trek is brought into the area few local services are used and there may be little financial benefit to the region.

If you trek independently you will contribute more to the local economy but perhaps not as much as you might think, since the few services you use (lodges and shops) are operated by only the more wealthy villagers. They do, however, provide a certain amount of work for local people as porters for provisions and as helpers in lodge kitchens.

Use local services The price of a Coke may be close to what you would pay in the West once you're several days’ walk into your trek but it's largely composed of the porter's wages required to get it up here. Buying drinks and other things from shops not only helps local business but also helps provide employment for porters. When buying things in the mountains try to buy goods from several shops rather than just from one. Patronize those shops that look as if they need your business.

Using lodges rather than camping is an obvious way to patronize the local economy. When arranging a trek with an organized group you could request to spend some nights in lodges rather than under canvas.

If you're trekking independently employ a local porter to carry your pack, if only over part of the trek. Unfortunately, most independent trekkers feel that being weighed down by a heavy pack is all part of the trekking experience. Perhaps colonial guilt (a British trait) also has something to do with it. Arranged once you're on your trek, the services of a porter can cost little more than £4/US$6.50 per day. it's safest to ask your lodge to suggest someone, rather than to go off with a total stranger. Ensure your porter is clear about your route and the number of days involved, make certain all porters have adequate clothing and shoes if you're trekking at altitude and be sure everyone is clear about what the pay includes. If you are going to be paying for food as well as a daily wage stipulate exactly what this includes. it's probably better to pay a slightly higher wage and not also pay for food and lodging except in remote places (Thorung Phedi and the Annapurna Sanctuary, for example) where everything is expensive.

Take care of your porter on the trail. As yet, it's not easy for independent trekkers to take out insurance against the death of a porter in their employ.

Observe standard charges To ensure a fair return for certain services lodge management committees have set prices for food and lodging that are listed on menus throughout each area. You should not attempt to bargain these down. don't, however, believe the curio sellers who tell you that all their goods are ‘fixed price�!

CULTURAL IMPACT

The people of the Annapurna region probably have a longer history of contact with the world outside Nepal than does any other group in the country. Pilgrims from as far away as South India have been visiting the shrines at Muktinath for hundreds of years. Thakali lodge owners have been providing food and shelter for Indian, Nepali and Tibetan traders on the great salt route along the Kali Gandaki for almost as long. The Manangba from the Marsyandi valley have been visiting distant Asian trading centres since the early 19th century when the king granted them special travel dispensations. Many of the men in the Gurkha regiments of the British and Indian armies come from villages in the south of the Annapurna region.

In the light of this history of contact with other cultures, the cultural impact of Western trekkers here is difficult to assess. Travelling in 1956, David Snellgrove visited many of the monasteries in the region and found most with almost as few monks as today's trekker will see. None had the large flourishing Tibetan-style communities that one might have imagined in the days before the trekkers arrived here.

Whilst for the older members of the villages on the main trekking routes, foreigners are probably nothing more than passing curiosities it is undeniable that we make a far deeper impression on younger Nepalis. Many now view West as best: Westerners are all rich, they can travel whenever and wherever they like and have girlfriends or boyfriends for casual relationships. It is unfortunate that Nepalis see us only when we are on holiday, intent on enjoying ourselves.

Encourage local pride Try to give Nepalis a balanced picture of life in the West. If they ask you what you earn, try to put this into perspective by telling them how much it costs to rent a flat or buy a car, an air ticket or a week's supply of groceries. Let them know what you think is good about their way of life – the incomparable scenery, the low incidence of robbery and murder, the clean air. If you've enjoyed your stay in a lodge or had a particularly good meal, let the lodge owner know.

Discourage begging Requests for ‘one rupee’, ‘bon-bon’ or ‘school pen’ from children or adults should all be ignored. Giving to beggars fosters an attitude of dependency. As ACAP's Minimum Impact Code (see box p85) states, ‘Begging is a negative interaction that was started by well-meaning tourists’. Giving sweets to children in a country with few dentists is not an act of charity. You may be approached by older children and asked to make a donation to their school. Whilst these requests may well be genuine, it's probably better to send a cheque, once you get home, to one of the aid agencies that operates in Nepal.

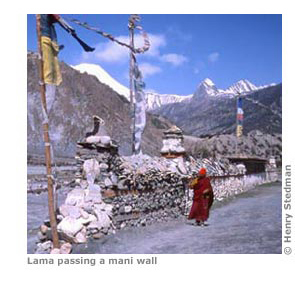

Respect holy places Always pass to the left of Buddhist monuments (chortens, prayer-wheels and mani-walls) and turn prayer-wheels clockwise. don't prop your pack (or yourself) up against a chorten or mani wall. Take your boots off before entering a temple and always make a donation. There's usually a donation box. it's also customary to give a small sum of money, or food, to sadhus, Hindu holy men whom you may meet on their way to Muktinath.

Dress and behave modestly Too many trekkers disregard local dress standards believing that Nepalis obviously don't mind what foreigners wear because there are never any complaints. Nepalis are far too polite to complain.

Women should wear loose trousers or calf-length skirts, not shorts or sleeveless blouses. Men should always wear a shirt and preferably long trousers; if you want to wear shorts these should be long shorts not jogging shorts. Avoid body-hugging lycra clothing and bright colours. Never bathe in the nude.

don't flaunt your wealth Your wealth, however poor you may be by Western standards, is way above the wildest dreams of most Nepalis so don't flaunt it. don't leave valuable items like cameras lying around.

Respect people's privacy when taking photos Before taking someone's photograph you should try to imagine how you would feel in their position. Always ask permission before taking a photo. don't pay people for posing, rather you should suggest sending them a copy of the photo and get someone to write down their address. If you do do this, however, it is most important to follow through your promise. A British anthropologist working in a small Nepali village was visited by a friend who took photos of a number of the villagers promising to send copies. Each day one villager would trek down to the post office to see if the eagerly-awaited package had arrived but it never did. To allay the tremendous disappointment the anthropologist had to take a set of photos herself.

Respect local etiquette Many of the do's and don't's concern parts of the body. The feet are considered the least clean or holy part of the body, the head the most. You should never touch someone on the head, not even children. Avoid sitting with your feet pointing towards another person but tuck them under you or point them towards a wall. don't step over someone or put yourself in a position so that they are forced to step over you.

Eating is done only with the right hand. The left hand is used for washing after defaecating so is considered unclean. When being given something, however, you should receive it with both hands. When greeting people don't shake hands but bring both palms together as if praying and say ‘Namaste’ (‘I greet the god within you�). don't point at things or people but extend your right hand instead. don't share eating utensils or take food from someone else's plate. When drinking from a container that is shared you must not let your lips touch it. High caste Hindus (Brahmins) have a particularly strict concept of food cleanliness (jutho) and as an untouchable (if you're from the West and not also a Brahmin) you will be served outside the house if you're eating there. you're unlikely to be invited to sleep inside the house.

don't play doctor Some local people along the trail may ask you for medicines or to treat wounds. Except in the case of cleaning up a small cut and applying a plaster you should direct them to the nearest health post. In the Annapurna region there's one in most larger villages. If you try to administer to anything more complicated than a small cut and your efforts are not ultimately successful you won't help to build up faith in Western medicine. Locals may continue to patronize the local shaman rather than the health post.

Always keep your sense of humour Nepalis very rarely lose their tempers and you should try hard to control yours when things aren't working out as you would wish. A smile costs nothing.

FURTHER INFORMATION

For more information on how to minimize your impact while trekking contact the Kathmandu Environmental Education Project (KEEP, see p119) or visit their website at : www.keepnepal.org. They provide advice on safe and eco-friendly trekking, and have an Information Centre in Kathmandu.

Trekking in the Annapurna Region

Excerpts:

- Contents List

- Introduction

- With a group or independently?

- When to go

- Minimum impact trekking

- Sample route

Latest tweets