Engagingly written — all the guides from this stable are first class

— Traveller

New Zealand - The Great Walks

Excerpt:

Sample route guide

Contents list | Introduction | Planning your tramp | Using this guide | Sample route guide | Sample track description

TONGARIRO NORTHERN CIRCUIT

TONGARIRO NORTHERN CIRCUIT

'Here you may see that heart bared, see the process of the making and moulding of the land by fire, ice and water. Mother Earth reveals her inmost secrets here, she pulses with never ceasing, sometimes fiery energy.'

James Cowan, as quoted in the DOC pamphlet Tongariro Northern Circuit

Introduction

In the heart of North Island lies Tongariro National Park. This spectacular volcanic park is full of unique lunar landscapes, surrounded by the fragile debris of old craters, extraordinary coloured lakes and steaming hot pools.

The Northern Circuit comprises a 49km tramp beneath intimidating volcanic cones amidst captivating lunar landscapes where you are afforded a glimpse of the earth at its creation.

Tramping between strange rock forms and around unusually coloured, striking landmarks, you are constantly surrounded by places where the Earth's energy steams and issues from vents and cracks – a place the photographer Craig Potton suggests TS Eliot might have described as a ‘still turning point�.

Youthful, temporary and ever-changing, this landscape reminds you of Nature's unpredictability and potential power.

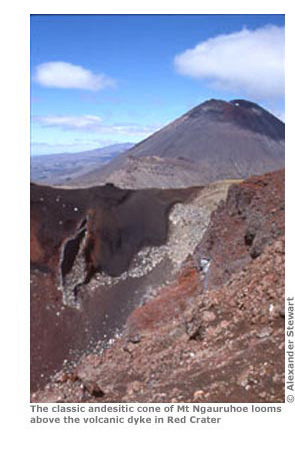

The tramp is centred on three large active volcanoes, Mount Ruapehu and Mount Tongariro with the high-tented cone of Mount Ngauruhoe forming part of the latter's volcanic massif.

This stunning triumvirate forms the roof of New Zealand's North Island. Mount Ruapehu (2797m/9174ft) is the highest peak on North Island. Mount Ngauruhoe (2291m/7515ft) is the most active volcano on the mainland. Mount Tongariro (1967m/6452ft) gave its name to the national park due to its special cultural significance to local Maori tribes.

History

Maori history and legend has always been intricately linked to Tongariro (see box opposite). Many early chiefs were buried on its slopes and the land came to be considered tapu, sacred.

Maori traditions dictated that no man could enter the region, in the belief that the mountain spirits would destroy him. They therefore actively sought to prevent anyone from ascending its slopes. They themselves would travel only as far as Ketetahi hot springs in order to bathe, but would venture no further.

In some circumstances the Tuwharetoa would refuse to even look at the mountain for fear of breaking its tapu.

Early European explorers were dissuaded from travelling in the area and risked the wrath of the Maori if they did so. However, in 1839 the botanist and explorer John Bidwell made the first European ascent of Mount Ngauruhoe.

Though rewarded with the knowledge that he stood where no other European had been, his insensitive actions greatly offended and angered the Tuwharetoa chief, Te Heuheu Mananui.

For the next twelve years, European explorers were kept away, until in 1851 the mountaineer Sir George Grey conquered one of Mount Ruapehu's lesser peaks, again without permission from the Maori guardians of the land.

However, it wasn't until 1879 that George Beetham reached the actual highest point of the mountain and in so doing saw Crater Lake for the first time.

By the 1880s a steady stream of explorers and geologists were descending on the region. As well as a fascination with the mountains themselves, Europeans were also interested in using the surrounding countryside for practical purposes.

In the late 1800s sheep were farmed in and around the Mangatepo Valley. However, inaccessibility, poor grazing and the difficulties of shipping wool out of the region all contributed to the demise of sheep farming in this area by the 1920s.

As well as pressure from Europeans, there were rival tribal claims to the land. Conflict was inevitable. After the New Zealand Land Wars, during which the Tuwharetoa sided with the rebel Te Kooti (see p51), rival tribes demanded the redistribution of the land by the Crown.

Te Heuheu Tukino IV, paramount chief of the Tuwharetoa, feared that this division of the land would result in the loss of their sacred volcanoes and a loss of mana for the tribe. In 1885 he declared

'If our mountains of Tongariro are included in the blocks passed through the court in the ordinary way, what will become of them? They will be cut up and sold, a piece going to one Pakeha and a piece to another. They will become of no account, for the tapu will be gone.

Tongariro is my ancestor, my tapuna, it is my head; my mana centres around Tongariro... I cannot consent to the court passing these mountains through in the ordinary way.�

In 1887, in a final bid to avoid the division of the land, Te Heuheu Tukino took the unprecedented step of giving the sacred volcanoes to the Crown and the people of New Zealand, to be turned into a national park in memory of his tribe, declaring ‘The mountains of the south wind have spoken to us for centuries.

Now we wish them to speak to all who come in peace and in respect of their tapu. His foresight and selfless action ensured that the land became New Zealand's first national park and only the fourth in the world, guaranteeing the preservation of the land and its heritage.

An act of parliament formally established the Tongariro National Park in 1894. Use of the land has evolved considerably over the intervening years but even now 'Tongariro still smokes ... the ancestral fires still burn and the land lives on for all ...' (Te Heuheu Tukino IV, 1887).

As the number of people using the park grew, so better access and accommodation was required. Between 1901 and 1903 huts were built at Ketetahi and Waihohonu.

The original 'Grand Tour' took people by paddle steamer up the Whanganui River to Pipiriki. Here they were collected by horse-drawn coaches and delivered to Waihohonu.

Railway services further opened up the region. The main trunk line was completed in 1908. This led to the development of the western side of the park and soon a road to the village of Whakapapa had been built.

The interest in skiing led to further developments. Numerous huts were built in and around Whakapapa, including the grand four-storey Chateau Hotel which opened in 1929.

Visitor numbers rocketed in the 1950s and '60s as roads were sealed, tracks cut and the area's reputation spread.

The original area gifted to the country amounted to 2630ha. This has been steadily increased by government purchase of surrounding land, and the national park now covers almost 78,000ha.

The unusual features and extraordinary beauty of the region led to it being awarded World Heritage status by UNESCO in 1990. Following this, the criteria for cultural sites was reconsidered.

Consequently, recognition was extended to areas that had spiritual and cultural value as well as to buildings or structures and thus, in 1993, Tongariro National Park was designated a Cultural World Heritage site as well, making it one of only a handful of places in the world to achieve dual status.

Geology

The andesitic volcanoes of Tongariro National Park lie at the southern end of the Taupo Volcanic Zone, the region of volcanic activity stretching from Mount Ruapehu through the Rotorua lakes to the continuously active volcano of White Island in the Bay of Plenty.

A tectonic plate boundary can be found just east of North Island, where the Pacific plate dips beneath the Indian-Australian plate, creating a line of volcanoes that extends from Tonga to Mount Ruapehu.

In geological terms, the Tongariro volcanoes are relatively young. They do, however, offer a graphic illustration of the phenomenal power generated by tectonic plate subduction.

Mount Ruapehu (2797m/9174ft) is a large, complex volcano that has developed from successive eruptions over the last 200,000 years or so. It is the highest point on North Island and still boasts the remnants of eight glaciers.

Although much diminished, particularly in the last 40 years, these glaciers once extended below 1300m and are the only glaciers left on North Island. Mount Ruapehu also boasts one of the world's few hot crater lakes that exists surrounded by permanent glaciers and snowfields.

It is certainly one of the world's most accessible hot crater lakes.

A huge eruption in 1945 sent ash clouds as far as Wellington. On Christmas Eve, 1953, an ice wall holding back Crater Lake gave way and an enormous flood of mud, volcanic debris and water, known as a lahar, swept down the Whangehu River devastating everything in its path.

It destroyed the Tangirai rail bridge moments before a crowded passenger train was due to cross, causing it to plunge into the valley below. One hundred and fifty-one people died in what remains one of New Zealand's worst ever disasters.

Almost fifty years to the day since the 1945 eruption, Mount Ruapehu burst into life again on 23 September 1995. Thousands of skiers witnessed a spectacular eruption as rock and ash sprayed from the crater.

Luckily the ski fields escaped damage, but lahars flowed down Whangehu, Mangaturuturu and Whakapapanui valleys, emptying Crater Lake completely. The volcanic activity lasted for three and a half weeks.

The lake began to refill until a large eruption on 17 June 1996 emptied it again. Ash, fire fountains and sonic booms all formed part of this dramatic eruption. Crater Lake has since refilled once more, although it may take up to twelve years to reach its previous level, future volcanic activity allowing.

Mount Tongariro (1967m/6452ft) is a very complex volcano. It is possible to determine eight craters in the massif, which measures 8km by 13km in total.

Mount Ngauruhoe (2291m/7515ft) is the youngest volcano of the three, probably about 5000 years old. Because of its young age, it has largely escaped the weathering effects of erosion and retains its perfect conical shape. Both Maori and geologists consider Mount Ngauruhoe to be part of the old Tongariro volcano.

Traditionally it has erupted at least every nine years, although it hasn't exploded since 1975. The most spectacular lava flows occurred in 1949 and 1954. The active Red Crater last emitted ash in 1926.

FLORA AND FAUNA

Flora

The vegetation in Tongariro National Park has evolved to survive in a wide spectrum of frequently harsh weather conditions. Temperatures range from mild to freezing, icy winds sweep the area's exposed sections and the vegetation must cope with extremes of rainfall, snow and in some areas even a lack of moisture.

Over 550 species of native plants are found in the park, around 80 per cent of which are endemic to New Zealand. Amongst them are 12 types of native conifer, 36 varieties of orchid and over 60 species of fern.

Vegetation in the exposed Rangipo Desert has evolved to exist under rocks or in cracks and crevasses. These areas offer some shelter from the battering effects of the wind. The plants have also developed long roots that search out water amidst the gravel.

Elsewhere, in moister sites, mountain shrubland dominates. Most of the plants here tend to be herbaceous. Tussock shrublands are populated by daisies, mosses, red tussocks and other species. Introduced heather is also taking a hold.

The forest sections are dominated by mountain beech. Forming a wide belt along the western and southern slopes of Mount Ruapehu, it's markedly absent from mounts Tongariro and Ngauruhoe.

Silver and red beech are here, primarily on the eastern slopes of Tongariro and the southern slopes of Mount Ruapehu. Unfortunately, their rigidity makes them prone to damage by heavy snowfall.

Rimu, kamahi and rata are also found scattered throughout the park, usually at elevations of between 600 and 900m (1960 and 2950ft). They support much of the insect- and bird-life found in the park.

Fauna

Despite its largely barren appearance, Tongariro is home to a deceptively wide variety of fauna. A broad range of birds, in particular, flourishes here, especially in the forested areas: North Island robin, whitehead, kereru, fantail, chaffinch, tui, tomtit, blackbird, yellow-crowned parakeet and kaka are all present. There are even a few North Island brown kiwi.

New Zealand's only native mammals, the short- and long-tailed bats, reside here, as do skinks and geckos, which are most likely to be visible during the warmer summer months. Cicadas, weta, huhu and caterpillars inhabit the forests.

Introduced species including hares, possums and red deer have made Tongariro their home too. They are responsible for damaging the alpine and forest vegetation and for modifying the native forest understorey through browsing.

PLANNING YOUR TRAMP

When to go

The climate in this region is strongly influenced by the prevailing westerly winds. It can be highly temperamental. As the moisture-laden clouds from the Pacific Ocean reach the mountainous volcanic plateau, they are forced to rise. This results in large quantities of rain.

Around 190 days a year are rain-affected, bringing up to 2500mm per annum. By the time the clouds reach the eastern side of the region, the Rangipo Desert, they have largely deposited the moisture they were carrying as rain or snow.

Consequently, the eastern region is a barren landscape of dark-reddish ash, largely devoid of vegetation.

Even though the prevailing winds are westerly, Tongariro is subject to all winds and conditions. There is no definite wet or dry season. Heavy snows accompanied by dramatic drops in temperature may occur at any time of the year.

The ideal time to tramp the circuit is between December and March when the circuit is usually clear of snow and the weather is less likely to be as severe. However, the weather pattern remains highly unpredictable and you must be prepared for all conditions, no matter what the initial outlook.

In winter, snow and ice make the circuit a difficult proposition, not to be undertaken lightly. However, with adequate clothing, the correct equipment and a degree of experience it is possible to visit and enjoy Tongariro at this time.

Sources of information

There's a DOC office at Whakapapa Visitor Centre (Private Bag, Mount Ruapehu; tel 07-892 3729, website whakapapavc@doc.govt.nz) that is ideally placed to offer advice and help you to prepare for your tramp. Open 8.30am-5pm on weekdays and 8am-5pm at weekends, they can book all accommodation and huts and supply detailed maps and pamphlets of the track. They also have a fascinating exhibition here recording the history and background of the area. There is also a DOC office in Turangi (Tongariro Taupo Conservancy, Private Bag; tel 07-386 8607, website ttcinfo@doc.govt.nz), which opens weekdays 8am-5pm and offers similar services. There's no i-SITE or visitor centre in National Park although there is a website, www.nationalpark.co.nz, covering most aspects of the town and the activities available around it.

Information centres in the main towns nearby can book huts and answer questions. Some may also be able to sell you the requisite mapping. Turangi i-SITE Visitor Information Centre (tel 07-386 8999, website www.laketauponz.com, PO Box 34), at Ngawaka Place, is open daily 9am-5pm; Ruapehu i-SITE Visitor Information Centre (tel 06-385 8427, website www.visitruapehu.com, PO Box 36) at 54 Clyde St, Ohakune, is open 9am-5pm on weekdays and 9am-3pm at weekends, whilst Taupo i-SITE (tel 07-376 0027, website www.laketauponz.com, PO Box 865) on Tongariro St, is open daily 8.30am-5pm.

Getting to the trailhead

Getting to the trailhead

The nearest reasonably-sized towns are Turangi to the north-east and Ohakune to the south-west. Tongariro National Park is well served by state highways. The famously scenic SH1 (the Desert Rd) on the eastern side of the park links Turangi and Waiouru. SH4 and SH47 on the western side of the park run from Taupo to National Park Village, via Turangi. There is also a regular passenger rail link, the Tranz Scenic Overlander (website www.tranzscenic.co.nz), between Auckland and Wellington that stops in National Park Village.

Although the Tongariro Circuit can be accessed from a variety of points, it is usually started from Whakapapa village or the Mangatepo road end.

Whakapapa village can be reached from Taupo or Turangi by catching the daily shuttle service operated by Alpine Scenic Tours or Intercity. If you are staying in National Park Village you will have access to several bus services that can shuttle you to Whakapapa or the Mangatepo or Ketetahi road ends. This service is primarily aimed at people attempting the Tongariro Alpine Crossing. Companies include Adrift Guided Outdoor Adventures (tel 0800-462 374, website www .adriftnz.co.nz), Adventure Headquarters (tel 07-386 0969, website www.adventure headquarters.co.nz), Howard's Lodge (see opposite), Plateau Shuttle (see Plateau Lodge p136), Tongariro Expeditions (tel 0800-828 763, website www.ton gariroexpeditions.com), Tongariro Track Transport (tel 07-892 3716) and Tongariro Volcanic Adventures (tel 07-892 2870, website www.npbp.co.nz) who operate out of the National Park Backpackers (see opposite).

There are several car parks in Whakapapa. From the village it is a three- to four-hour walk to Mangatepo Hut. By starting at the Mangatepo road end, it is only a thirty-minute walk to Mangatepo Hut. Should you wish to access the circuit from another area, your options are twofold. Either begin from the Ketetahi road end car park, which is a two- to three-hour walk from Ketetahi Hut, or from the car park just off SH1, a 60- to 90-minute walk from Waihohonu Hut.

Hitching throughout the park is difficult as traffic on the roads is fairly light.

Visitors are advised not to leave valuables in parked cars and to make all transport arrangements before setting off. For a full list of current operators, times and routes contact the DOC office in Whakapapa.

Local services

The small hamlets and towns in the Tongariro area are scattered and fairly remote. You are best off staying in either Whakapapa or National Park Village.

Whakapapa boasts a small food store, a petrol station, a café, pub, the visitor centre (see p133) and several places to stay. Try the Holiday Park (tel 07-892 3897, website www.whakapapa.net.nz; tent pitch NZ$17/10 per adult/child, dorm NZ$25, cabin from NZ$60-70, self-contained units from NZ$84-99), Skotel Alpine Resort (tel 07-892 3719, website www.skotel.co.nz; backpacker wing dorm NZ$30, sgl/twin/dbl with facilities or tpl NZ$40/55/80, hotel dbl from NZ$130), a wooden complex with sauna, spa, gym, restaurant and bar, or the stately Bayview Chateau Tongariro (tel 07-892 3809, website www.chateau.co.nz; dbl from NZ$190, suite NZ$250-1000); opened in 1929 this grand neo-Georgian mansion is spectacular to see and offers the lavish facilities and classy service you'd expect to find in one of New Zealand's most renowned hotels.

Around 15km from Whakapapa, the small community of National Park Village (see map p136) spreads out from a crossroad junction linking SH4 and SH47. It has a petrol station and small shop, some very congenial bars, a railway station and a selection of hostel-style accommodation.

The friendly National Park Backpackers (tel 07-892 2870, website www.np bp.co.nz; tent pitch NZ$14 per person, dorm NZ$26-31, twin/dbl NZ$67-86), on Finlay St, has a well-equipped kitchen, spa pool and its own 8m-high indoor climbing wall boasting more than 50 different routes; the comfortable Ski Haus (tel 07-892 2854, website www.skihaus.co.nz/; tent pitch NZ$12 per person, dorm NZ$19-21, dbl/twin NZ$58), on Carroll St, has a spa and ‘conversation pit’ for guests to hang out in when not at the bar or in the sociable restaurant. The excellent Howard's Lodge (tel 07-892 2827, website www.howardslodge.co.nz; dorm NZ$26-27, dbl or twin NZ$68, en suite NZ$85, suites from NZ$140), on the same road, has accommodation for all budgets, two spacious lounges with log fires, a pool table and free spa as well as a decent outdoor shop and info service where you can book onward buses. On Millar St is the spacious Pukenui Lodge (tel 07-892 2882, website www.tongariro.cc; dorm NZ$20-26, dbl/twin NZ$65, en suite NZ$75, chalet from NZ$180). There's also the cosy, well-equipped Adventure Lodge (tel 07-892 2991,website www.adventurenationalpark .co.nz; dorm NZ$25, dbl/twin NZ$65, motel unit from NZ$130), on Carroll St, with rooms to suit most budgets, two hot spa pools, an open log fire and a large covered BBQ area. They offer a number of good value deals on accommodation, meals and transport to and from the Tongariro Crossing.

Huts and campsites

There are four huts on the circuit. From October to June you must have a Great Walks hut pass if you intend to stay at Mangatepo, Ketetahi, Oturere or Waihohonu huts.

A pass entitles you to spend a given number of nights in the DOC facilities on the track from the date of issue. It is best to buy your hut pass in advance, from local visitor centres or DOC offices, in order to avoid the higher premiums charged by the wardens.

The huts are supplied with bunks, mattresses, toilets, rainwater, gas heating and gas stoves (stoves are available only during the summer months so you must carry portable cooking gear at all other times of the year).

There is usually a warden on duty in each hut during the peak season providing information and regular weather updates as well as to check hut passes. Maximum group size in the huts is twelve per group.

Outside the summer season, the huts are not serviced and off-season rates apply.

Campsites have been established near each of the huts. A Great Walks pass is still required for camping. The adult hut fee for the summer season is NZ$25 and NZ$15 for the rest of the year; the camping fee is NZ$20 and NZ$5 for the same periods. There is no charge for children or youths.

Maps

The best maps for this area are the 1:80,000 scale Tongariro Parkmap (273-04) or the 1:50,000 scale Tongariro (T19) by Topomaps. These can be purchased at DOC offices and information centres around the region.

Distances and times

The three- to four-day circuit follows a well-marked route. Although not unduly taxing, it can become difficult if weather conditions deteriorate. However, even in poorer conditions the track is still visually stunning.

Take your time on each section in order to appreciate better the land's power, its rugged terrain and stark, desolate beauty.

Whakapapa village to Mangatepo Hut - 9km, 3-4 hours

Mangatepo Hut to Ketetahi Hut - 10km, 4-5 hours

Ketetahi Hut to Oturere Hut - 8km, 3-4 hours

Oturere Hut to Waihohonu Hut - 8km, 2-1/2�3-1/2 hours

Waihohonu Hut to Whakapapa village - 14km, 5-6 hours

New Zealand - The Great Walks

Excerpts:

- Contents list

- Introduction

- Planning your tramp

- Using this guide

- Sample route guide

- Sample track description

Latest tweets